How to Craft More Melodic Solos

Take a moment and think of your favorite guitar solo. Can you hear it in your head, note-for-note perfect as if you were listening to the track itself? I’m willing to bet the answer is yes. Indelible guitar solos tend to get lodged in your brain that way. Every practicing guitarist not only strives to play these solos as well as the guitar heroes who composed them, but we all long to craft such a brilliant lead ourselves. The million-dollar question is: Where do you begin when attempting to play the next great, iconic solo? The next “Stairway to Heaven” or “Kid Charlemagne” or “Hotel California”?StructureWhen it comes to creating an iconic guitar solo from scratch, structure is everything. Though the three classic solos named above are wildly different in tone, style, and nearly everything else, one thing they all have in common is a clear, concise structure. Structure can be dictated by a number of factors. For instance, the structure of your solo could be dictated by the form of the song itself. If the form in the accompaniment changes as your solo progresses, as it does in countless songs (including one of my all-time favorite solos, George Harrison’s lead on “Something”), the structure is pretty much laid out for you. It’s just a matter of letting the song take its course and following along. On the opposite end of the spectrum, if you are simply playing over a loop of a single riff or chord progression, the structure of your lead then falls entirely on your shoulders. How do you create a sense of structure where there is none?Motivic DevelopmentThe cornerstone of melodic writing is the motif, which is defined as a brief melodic or rhythmic idea used as the basis for a larger musical composition. When soloing, having a motif to develop over the course of your solo—or even just having one to fall back on after you melodically deviate from it—can come in very handy. By using a motif (or even several motifs), you immediately ground your lead and give the listener something familiar to recognize and latch onto. To be an effective and melodic soloist, it’s important to know how to skillfully develop a motif. Ex. 1 shows a solo over a 12-bar blues in the key of A, starting with a simple motif. Over the rest of the solo this motif is developed in several variations that get progressively complex.You can also leave motifs as musical breadcrumbs—little ideas that pop in and out, with or without variations, to provide a sense of unity to a solo that is otherwise through-composed, or played without depending on motivic development. A great example of this approach is David Gilmour’s iconic “Comfortably Numb” solo, which features several pentatonic motifs with slight variations in the course of awe-inspiring through-composed blues phrasing. Ex. 2 is based around the chord progression from “Comfortably Numb” in the key of B minor. A simple pentatonic motif is introduced in the first measure, then is reintroduced and built upon in measure four. The rest of the solo between this motif and its variations is through-composed, à la Gilmour’s breathtaking lead.ArticulationWhen we think of melody, we typically think of the human voice as the instrument of choice. So naturally, a great place to start when learning to solo more melodically is to understand how vocalists interpret melody. Vocalists practically never hit a note straight on with no inflection. Good vocalists know how to embellish a melody through articulation. Great vocalists know how to control every aspect of every note to get the most out of it. To be a better, more melodic soloist, you need that kind of control.The way you play a note is as important as the note itself. Therefore, it’s always a good idea to practice articulating your phrases in as many ways as your hands can conjure. For guitarists, this means incorporating techniques like string bends, slides, hammer-ons, pull-offs, and vibrato. Ex. 3 shows a simple A major pentatonic (A–B–C#–E–F#) melodic phrase, first played without any articulation, then reinterpreted several times using a variety of articulations. Because the way these notes are played is completely different in every case, each lick has a slightly different flavor. Try this with any lick in your arsenal. Use these articulations in as many ways as you can dream up. Be creative.The Final FrontierSpace is often the unsung hero of great leads. Brief stretches of musical silence not only emphasize the phrases that immediately precede them—thus giving listeners a chance to process what they’ve just heard—but they create anticipation for what is to come next. Many guitarists (myself included, until I came to the above realization) try to fill their solos with as many ideas as they can, leaving absolutely no room to breathe. This everything-but-the-kitchen-sink approach often leaves listeners cold because they’re never given a chance to process what they’re hearing. I liken it to listening to someone speak who doesn’t know how to end a sentence or stop to take a breath. You’re quickly going to lose the thread of what they are saying, and eventually you’re going to stop caring about what they had to say in the first place.Guitarists are notoriously afraid of silence. When I was struggling with this problem in my musical adolescence, I was afraid that listeners would think I was running out of ideas if I wasn’t playing something at any given moment. But on the contrary, incorporating space into your leads shows that you have supreme confidence in your playing and musical choices.The Arc of Your LeadThink of your solo as a story you want to tell. Every good story needs a beginning, a middle, and an end. A great solo is bound by the same rules. You need a starting point, some rising action, a climax, and ultimately a conclusion. This boils down to movement. If your lead languishes in the same place for too long, you risk losing the listener’s interest, so you have to build momentum in your solo. There are a number of ways to do this, including speeding up the rhythm of your phrasing and guiding your phrases up or down the neck. A common arc in great solos finds the player gradually working up from a low point to a high point, either in terms of pitch, complexity, or rhythm, or some mix of the three. Jimmy Page’s “Stairway to Heaven” solo is a perfect example of this. He starts the solo in 5th position, briefly moves up the fretboard, then back down, then a little further up, back down, and so on in that fashion, inching his way up the neck a little further each time until he makes the triumphant leap up to the 17th position for that iconic 16th-note-triplet pull-off lick to finish it out. I’m pumped up just thinking about it! If you were to transcribe Page’s solo and draw one continuous line through each and every notehead, the line would move up and down in a wave-like fashion, showing lots of melodic interest when you zoom in on any given measure. But if you zoom out and look at the lead as a whole, you would see the arc of the entire lead starts low, works its way up and up, fakes you out for a second by dipping down right before its climax, and then jumps to its ultimate peak. I honestly can’t think of a more impeccable command of compositional structure in all guitardom than Jimmy Page’s solo on “Stairway to Heaven.”If you keep all these things in mind, you’ll be cooking up stellar leads worthy of your guitar heroes in no time!

Read more »

The “Stairway” Progression

From the 12-bar blues to a shuffle pattern to a IIm7–V7–I progression, many musical motifs get recycled and repurposed. It’s accepted that these ideas are simply out there in the air for songwriters and composers to use, gratis, as musical building blocks from which to create new work. Right?Maybe not. A few years ago, Led Zeppelin was sued for using one of these common motifs as the basis for “Stairway to Heaven.” I was as surprised as anyone. I’ve been teaching this chromatically descending minor chord progression as an example of a compositional tool for years, citing a series of examples of its use in different situations. But sure enough, the band Spirit had decided to lay claim to the progression.During the trial in 2016, Jimmy Page admitted that his song and Spirit’s “Taurus,” “are very similar because that chord sequence has been around forever.” Back when Page wrote “Stairway” in 1971, he was surely well aware of what he was doing. This chord progression had really been making the rounds in pop culture.I’ve collected quite a few examples of this progression’s usage to show what can be done with this motif, compositionally. These examples prove that this progression is nothing more than a kernel of musical information that songwriters and composers have been using for much longer than “Stairway to Heaven” or “Taurus” have been around.The list below could be much longer, but I’ve edited it down to what I think are the strongest examples, where this motif is used in the most recognizable way, either as the beginning of a song or a section. So, you won’t be seeing “You Are the Sunshine of My Life” by Stevie Wonder or the “Dead Man” theme by Neil Young, but just know that both of those songs are among the many that use this pattern.Because both “Stairway to Heaven” and “Taurus” are in A minor, I’ve decided to transpose all the examples into A minor to make it easy to compare them. But first, let’s hear both “Stairway” and “Taurus.”Stairway to Heaven (Remaster)TaurusIn Ex. 1, we see the opening phrases to both “Stairway to Heaven” and “Taurus.” The first three measures are the only overlap in these phrases. Both songs have a descending bass note that starts on the root of Am, then descends chromatically to F. This bass line creates some interest in what could be a rather stagnant stretch of Am. The F# can be used as either an Am6/F# or a D/F#. Essentially, the difference between names here is based on what else happens harmonically around that chord and for our purposes, we can consider them to be the same chord.Following the F# bass note, both songs have a measure of Fmaj7 and that’s where the commonalities end. “Stairway” follows that with a resolution from G back to A minor, which would be a bVII resolving to a Im, while “Taurus” goes to Dm, which is the IVm chord.If we go way back in time to the 17th century, we find Italian Baroque composer and guitarist Giovanni Battista Granata featuring this motif in his “To Catch a Shad.” In the trial, Led Zeppelin used this song as proof that the chord progression is in the public domain. Shown in Ex. 2, the song uses essentially the same progression as “Stairway to Heaven.” “To Catch a Shad” was covered by the Modern Folk Quartet in 1963.To Catch a ShadFast forwarding to the 20th century, we discover that Irving Berlin used this same motif for the first four measures of his song “Blue Skies” in 1926, shown here in Ex. 3. The progression descends chromatically to a D major chord, then modulates to C major for the next phrase.Thelonious Monk used “Blue Skies” as the basis for his song “In Walked Bud,” first recorded in 1947. The first four measures are essentially the same, followed by a similar turnaround through a sequence of chords in the key of C major.Irving Kaufman – Blue Skies (1927)In Walked BudBoth Duke Ellington and Richard Rodgers used this progression in the 1930s for their respective compositions “In a Sentimental Mood” and “My Funny Valentine.” In Ex. 4, notice how Ellington used the progression, then repeats it up a fourth. The next phrase begins back on the Am chord and resolves to a C major.Rodgers’ “My Funny Valentine” follows the descending line down to F (much like Spirit would later do), and goes to Dm, before a IIm7b5–V7b9 turnaround back to the tonic.The Beatles never shied away from using a clever songwriting maneuver and our progression in this lesson is no exception—just check out Ex. 5. In 1963, they covered the song “A Taste of Honey” on their debut, Please Please Me. Composed in 1960 by Bobby Scott and Ric Marlow for the Broadway play of the same name, the song features a chromatically descending minor progression in the beginning of the verse.This progression must have made its mark on the budding songwriters, because Paul McCartney and John Lennon wrote “Michelle” for 1965’s Rubber Soul and used a two-measure descending minor progression as the intro, followed by a measure of IVm and V.A few years later, George Harrison used the progression in “Something” from 1969’s Abbey Road. This progression occurs in the verse when Harrison sings, “I don’t want to leave her now,” before coming back to the song’s signature turnaround lick. An interesting thing about “Something” is that the verse opens with the same type of harmonic move on a C major chord. So, the first chords are C–Cmaj7–C7.A Taste Of Honey (Remastered 2009)Michelle (Remastered 2009)Something (Remastered 2015)Ex. 6 shows the first phrase of the song “Chim Chim Cher-ee,” written for the 1964 Disney film, Mary Poppins, by brothers Robert B. Sherman and Richard M. Sherman. Heavily covered by jazz artists in the mid ’60s, this song was most certainly floating around in the popular consciousness. The first two measures are followed by a resolution (IVm–Im) and a turnaround (II7–V7).Also from that same year was “War of the Satellites,” written for the Ventures’ In Space record by Danny Hamilton. In this surf rock classic, the descending minor progression is used in A minor, modulates down a whole-step and repeats in G minor, then modulates again to F minor, where it stays momentarily then jumps around chromatically, ascending and descending, before repeating.Mary Poppins – Chim Chim Cher-eeThe Ventures War Of The Satellites (Stereo) (Super Sound)Through these examples, we’ve looked at quite a wide variety of styles, from baroque music to Tin Pan Alley, jazz to surf, show tunes to classic rock. What’s fascinating about all of these examples is the way the songwriters were able to take this common piece of harmonic information, put a unique spin on it, and go in different musical directions.This article was updated on September 20, 2021

Read more »

Should You Keep a Guitar Journal?

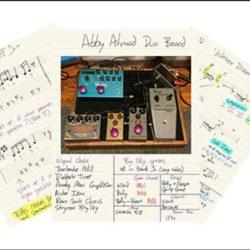

Last updated on July 22, 2022Musical research is an incredibly important aspect of growing as a musician. We’re already subconsciously absorbing information when we listen to music—even if it’s in the background. Documenting what we’re hearing can really solidify what we take away from the listening experience.As musicians, we are sound. Everything we hear influences us, but the way we collect sounds can resemble how we might collect receipts for tax purposes: They’re just scattered all over the place. If that’s the case, when April comes around you suddenly wish you had a system for finding your receipts, organized by category, in one central location.Our musical minds are similar to our households at tax time. You hear so many musical ideas but they’re completely unorganized. I started thinking about how to categorize my favorite musical ideas because I wanted to collect and record what I found influential. This led me to musical journaling.The Musical JournalMy musical journal is a notebook where I write down musical ideas that I find appealing. I don’t make full song transcriptions. Instead, I highlight small phrases, a progression, or other details about a song. I make notes about how they work and what I like about them.It’s less a personal Real Book and more of a recipe book. When most musicians transcribe, they often notate much longer sections or ideas. My musical journals are filled with smaller snapshots.The GoalMy goal is to have a physical reference of ideas that inspire and appeal to me. I consult the journal when I need to play a certain style of music or jump-start some creativity. Musical styles tend to have specific elements and if you want to get deep into a style, you must get good at recognizing its traits.For instance, I have a journal on punk music. It includes notes on my favorite punk songs from the Buzzcocks, the Clash, the Ramones, the Germs, the Dead Kennedys, Minor Threat, and Black Flag, to name just a few. When I need to play a punk gig or session, or want to compose in that style, I’ll go through my punk journal to see what progressions or chord shapes are common. Punk music uses a lot of full barre chords. If you play the right punk chords with the wrong voicings, it won’t sound like punk.Different JournalsBack to organization. I keep a different journal for each style of music I’m researching. I have one for funk that includes songs by the Meters, Funkadelic, and Sly Stone. I have another for blues with research on Howlin’ Wolf, Mississippi John Hurt, Bukka White, Muddy Waters, and others.Because I listen to and am asked to play different styles of music, my research tends to be broad. Although I would encourage you to listen to many different types of music, it’s not necessary to journal about everything you hear.Here are just a few examples of things I like to include in my journals.Song Tempo Many musicians don’t make notes on song tempos, yet the tempo is incredibly important to the feel of a song. Changing a tempo by merely 2 bpm can greatly alter its sound and feel. If you study a specific style of music, you may also notice that a lot of it lives in a tempo neighborhood. Being aware of this can deepen your playing. In Fig. 1, you can see a page out of my journal about a song called “Western Dream.”Chord Cycles When researching styles of music, you will find similar chord cycles. Musical styles are like families, and chord progressions typically have a direct relationship to other songs in that genre. You’ll see a lot of I–IV–V progressions in the blues, for example.Riffs Guitar riffs also tend to get recycled. As with chord progressions, it might not be the identical riff, but it may sit in a similar position and use a closely related collection of notes.Understanding these riff positions or collections is important. For instance, I’ve seen a lot of guitarists who study blues play the correct notes, but in the wrong position. Why does this matter? For one thing, the note’s timbre can be different, depending on what string it’s played on. For another, the position and fingering give you access to certain expressions like bends, hammer-ons, and pull-offs.When I’m journaling, I note the position the riff is played in (Fig. 2). And it may vary considerably from where I play a similar riff in a different genre.MelodyI know I just talked about positions and fingering, but I think too many guitarists look at music as a matter of positions on the fretboard. I can’t stress enough the importance of melody. One of my favorite things to do with students is to study the melody line of a song. It’s great for building good soloing skills.Melody lines often give you everything you need to create a tasteful solo. Sometimes I’ll journal a melody line to a verse or chorus (Fig. 3). Then I’ll make notes about the melody’s relationship to the chords. Does it start on the 3 of the chord? Are there any interesting color notes in there that stick out to you?It’s a great idea to take note of these things. These are sounds you might like to use in a different song. Understanding the melody’s relationship to the chord is vital: Don’t look at notes and positions in isolation, but rather in a melodic context. You only truly understand the flavor of a note when it’s set against another note or a chord. These are like flavor pairings. Just as some pair white wine with fish, you may pair an E note in a melody with a C chord.FormAnother corner guitarists paint themselves into relates to understanding song form. Many players start by learning sections of songs, but if you’re not looking at the whole form of a song, you’re seeing an incomplete picture.Form dictates many musical decisions. You can’t fully understand why some of these decisions were made unless you look at the song as a whole. I mentioned not transcribing full songs in my journal, but I do mark out the form for reference and make mention of songs that have an unusual layout.Consider “I Wanna Be Sedated” by the Ramones. It modulates up a whole-step after the first chorus. This is an interesting move—not many songs modulate that early.ToolsThere are several ways you can approach journaling. For instance, you can use a traditional notebook. I used to pursue journaling like an arts-and-crafts project. I had blank sheets of music paper and a wire-bound notebook. I’d notate a musical idea on the sheet music, cut it out, tape it into the notebook, and then write my notes around it.I found this somewhat meditative. It forced me to take time to write it, cut it out, and tape it. I’d think about the music more before moving onto something else. Each entry wasn’t a brief moment, but rather a process to be experienced.And although I liked it, it was a little difficult to do consistently on tour. I needed to have a book bag with several notebooks, scissors, tape, and blank music paper. I’d sit in my hotel room and research music and make a mess.To reduce what I needed to carry around, I moved to an iPad. There is a wonderful app for the iPad called GoodNotes. It includes templates for sheet music, tabs, and ruled paper. It allows me to have a collection of journals, just as I would with a notebook. I can create a transcription and cut and paste it in my journal. I can write notes in different colors and highlight them.Memory ManI’ve always been fascinated with music, but my memory isn’t always the best. I can remember songs on tour and during a session, but fishing a song or idea out of my memory archives can be a little time-consuming. That’s why I always have my research with me: If I’m on a session and ask to play a reggae-like single-note line, I can open up my notes on reggae and check out my Max Romeo research.Reading MusicYou don’t have to read music to keep an effective music journal. It doesn’t matter so much how you make your notes as long, as they are well-documented and clear, and make sense to you.I personally like reading music and understanding music theory. Which isn’t a surprise, since I wrote a book on the subject called Practice Makes Progress. It helps me understand and recall things more quickly. I can spot similarities and apply them to other situations more effectively. I don’t use theory to create music, just to connect a few dots.SoundsIt’s also a great idea to include a song’s sounds in your journal notes. Is there a wah? A specific fuzz tone? A particular guitar or pickup position? I write down these tone recipes for future reference.Gig JournalOn the subject of sounds, I also journal about guitar rigs for the various gigs I do. Taking pictures of pedalboards, amp settings, and guitars can really help you get back up to speed on a gig you haven’t played in a bit. Guitarists tend to be a tweaky bunch. We’re always trying new pedals and messing with settings, but sometimes we need to turn back the clock.I don’t know about you, but I can’t remember what I used two gigs ago, let alone four or five. I play with a lot of artists and do a wide variety of sessions. Each of these gigs has very specific tone collection and I don’t use the same gear for every gig. I can either scratch my head for an hour or take one minute and look at my notes. I will also include notes on what presets I used for which song. If you haven’t been gigging regularly with a particular artist or band, don’t expect you’ll remember preset six for the fourth song in the set in eight months ago.Fig. 4 is a page from my journal for Amy Helm. I tour with Amy a lot, but sometimes we have a few weeks off. During this hiatus, I’m likely to change pedals and do different gigs. Even if I know what pedals I used on an Amy’ gig, I still might not remember the exact settings on my Vick Audio ’73 Rams Head. Tracking down a photo in my photo library can also be tricky.In the break from the last Amy Helm tour I played a gig with songwriter Abby Ahmad (who also happens to be my wife). They may share a few pedals, but it’s a very different sound and approach (Fig. 5). Having some assistance with gig recall allows you to make more music, more confidently.Okay, now I think you have some work to do.

Read more »

The Two Commandments of Shredding Chromatics

Chops: Advanced

Theory: Intermediate

Lesson Overview:

• Understand how to phrase “outside” notes.

• Learn how to add tension to speedy passages.

• Strengthen your alternate-picking technique.

Click here to download a printable PDF of this lesson’s notation.

In my earlier years as a guitarist, I was intimidated by the idea of expanding musical lines with notes that weren’t in the scale that was diatonic to the progression or chord I was playing over. What helped me get pass this fear? Studying how some of my favorite players incorporate non-diatonic notes in a systematic way. In this lesson, I’ll share some of the ideas I discovered. We’ll explore the concept of chromatic playing and see how you can include non-diatonic notes in your phrases. I’ll examine how a couple of my favorite players have used the chromatic concept—Steve Morse (Dixie Dregs and Deep Purple) and Ian Thornley (Big Wreck). I’ll also show you an example of how I incorporated chromatic playing into a solo from one of the songs on my latest album. Okay, let’s get started.

First off, let’s define the term chromatic. A quick internet search gives us this definition: Music relating to or using notes not belonging to the diatonic scale of the key in which a passage is written.

When we think of using notes that are outside of a given key, it’s easy to think they sound wrong or that we’ve made a mistake. Well, that could be the case, but it’s also possible to use those “outside” notes in a musical way. So how do we use chromatic notes musically? One way is to use chromatic notes to “fill in” spaces between the diatonic scale tones.

For instance, if we were playing an A minor pentatonic (A–C–D–E–G) scale, it would be easy to simply fill in the notes between the root (A) and the b3 (C). An important thing to remember: Don’t dwell on the chromatic, or outside, notes. Instead, emphasize the diatonic notes.

You can accomplish this by playing chromatics with shorter note values or just as part of a faster musical line. Aim to land on the diatonic notes on important rhythmic points in your musical lines—possibly on downbeats or even the “and” of a beat when dealing with 16th- or 32nd-note passages.

Using some musical examples, let’s take a look at how the aforementioned players handle this.

First up is the incredible Ian Thornley. We’ll dissect a musical line reminiscent to a phrase from his solo on the Big Wreck song “A Million Days.” In Ex. 1, I simply outline the G# minor pentatonic (G#–B–C#–D#–F#) scale that Ian seems to be using as a foundation for the solo.

Click here for Ex. 1

Ex. 2 illustrates how he fleshes out the musical idea by using many chromatic notes. Ian does two things: He plays the chromatic tones very quickly and doesn’t dwell on any of them. Also, he lands the diatonic notes on the more important beats. Because he’s playing the line using 16th-note sextuplets, those points would be the first and fourth note of each group of six. Only once does he play a chromatic note on an important beat, but he gets away with it because of the sheer speed of the line.

Click here for Ex. 2

Now let’s see how Steve Morse uses similar concepts. I’ve chosen several lines similar to what he plays in “Simple Simon.” In Ex. 3, I simply outline the G minor pentatonic (G–Bb–C–D–F) pattern that underlies the next phrase.

Click here for Ex. 3

Ex. 4 shows how Steve uses the concepts we’ve discussed. One interesting point: Steve adds tension to the first 16th-note line by starting on C# over the C5. This creates a unique sound, and since Steve keeps this line moving until ultimately resolving by landing firmly on G, it works out well. In the faster sextuplet line that closes out the example, Steve passes very quickly through the chromatic notes and lands the diatonic notes on the important beats.

Click here for Ex. 4

The final musical examples are from “Twisted Impression,” a song from my latest album, Brief Eclipse. In Ex. 5 and Ex. 6, I outline the scale fragments of A minor pentatonic and A Dorian (A–B–C–D–E–F#–G) that I use as my foundation scales.

Click here for Ex. 5

Click here for Ex. 6

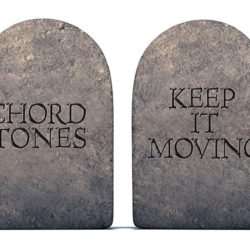

In Ex. 7, we have an Am–C progression with a long 32nd-note line that uses the same two principles that popped up in Steve and Ian’s lines: chord tones on strong beats and keep it moving!

Click here for Ex. 7

Ex. 8 demonstrates a simple A minor pentatonic shape that’s great to have under your fingers.

Click here for Ex. 8

Finally, Ex. 9 is a pretty twisted line that wraps up everything we’ve talked about in this lesson. Even though we’re hearing a stream of 32nd-notes, our ears latch onto the tones that land on the strong pulses.

Click here for Ex. 9

I hope these examples can help you incorporate chromatic sounds into your soloing and spark some new and inspiring ideas.

Read more »

Did Robben Ford Invent a Scale?

I’ve gleaned so much from listening to Robben Ford’s music. His incredible understanding of blues harmony and jazz vocabulary has been a deep inspiration. Over the years I’ve come to discover the “Robben Ford” scale. Of course, he didn’t invent it, but he has taken this sound and created a lifetime of music from it. Simply put, it’s a minor pentatonic scale (1–b3–4–5–b7) where the b7 is replaced with a 6. In the key of A, this would be A–C–D–E–F#.Often the first scale many blues and rock guitarists learn is the minor pentatonic, so adjusting one note to create a new sound is fairly easy. The RF scale has the benefit of jazzing up the blues a little, yet it’s still very familiar and firmly rooted in the style. All examples for this lesson will be in the key of A.Ex. 1 shows the five main positions of the scale as fretboard diagrams, and also in music notation and tab. It is critical to become familiar with this material before proceeding further. I’d suggest starting with position 1 and running the scale many times until you can play it without any thought, in as many ways as possible. Once you’re comfortable with position 1, move on to position 2, then 3, etc.Now we need to hear how the scale works in context. In Ex. 2 you can see (and hear) how the RF scale sounds over the I chord (A7) of our A blues, and has the effect of implying an A13#9.One of the benefits of using the RF scale instead of the regular minor pentatonic or blues scale is that it sounds “more correct” on the IV chord. Remember, we’re playing blues in the key of A, so the IV is D7. In this context, the RF contains the 3 (F#), b7 (C), and 9 (E), which implies a D9 sound. The chord’s 3 is critical to defining its sound. The standard minor pentatonic has the 4 of the chord and therefore implies a need to resolve. In Ex. 3 you can hear how these notes line up over a D7 chord.Ex. 4 shows the sound of the RF scale on the V chord, which in this case is E7. Over this chord, the notes function as the 11, #5, b7, root, and 9, and this implies a E9#5 sound. It’s interesting to hear how the 11 works well over the V chord. That’s because the V always wants to resolve, typically to the I chord.Ex. 5 is a 12-bar blues progression in the key of A with typical changes. The brackets show the chord changes that would be implied when using the RF scale over this chord progression. Note, while the implied chords lean toward jazz, they don’t tip too far in that direction, and this keeps the sound still firmly rooted in the blues. This is a key element of Robben Ford’s playing.If the theory is starting to sound a little too heavy, don’t worry—the principal is simple: Take the A minor pentatonic scale and replace every G with an F#. Boom, you have this new hip sound which is very usable.Our first phrase in Ex. 6 starts off with a swinging Am6 arpeggio (A–C–E–F#) before moving into a bluesy bend of the 3 and then resolving to the root. Notice how many chord tones are on strong beats. Even when dealing with extended harmonies, it’s always good to reinforce the essential sound of the chord.We focus on the IV chord (D7) for the lick in Ex. 7. The addition of the F# to the scale is really the key here. Again, aim for the chord tones on the strong beats and you can’t really go wrong.In Ex. 8 the harmony moves from the V (E7) to the IV (D7). The slight differences in the pattern from measure one to measure two are emphasized by the rolling triplets. This is a great way to build tension before the release back to the tonic (A7) in the final measure.There’s plenty of space in the first measure of Ex. 9. Leaving space is an essential element of blues phrasing, and listening to such giants as B.B. King and Albert King will give you plenty of inspiration for when to lay out. The quarter-step bends in the second measure will require some practice to get just right. Aim for a sassy feel that’s slightly out of tune, but in control.The next lick in Ex. 10 works great in measures five through eight of a 12-bar blues. After establishing a simple motif in the first measure, the second measure alters it just enough to keep the listener engaged. Such motivic development happens all the time in blues solos, so keep an ear out for it.Finally, Ex. 11 is a lick that would work great as a cadenza at the end of a tune. The rhythmic idea of triplets should almost always be felt in any swing-style phrase. Here, I use a pattern similar to Ex. 8 to descend to the root.So, there you have it—a new sound with minimal effort. Isn’t that the best way to learn? Take something you already know and expand it to create new material. Next time you’re at a jam session, give this scale a try, as someone will almost always call a blues.

Read more »

Twang 101: Bluegrass Goes Electric!

Those who haven’t investigated bluegrass might write it off as simply another branch on the country music tree, but there’s so much more to dig into. Born out of the Appalachian mountain regions, bluegrass is the exciting meld of Irish and Scottish folk music with gospel, jazz, and blues elements. It’s a genre dominated by high-level playing on a variety of instruments, including flattop steel-string guitar, fiddle, banjo, mandolin, and Dobro.There have been many bluegrass guitar icons, from the pioneering Doc Watson, Clarence White, and Tony Rice, to such modern masters as Bryan Sutton and David Grier. Today, younger players like Molly Tuttle and Carl Miner keep the genre alive.Traditionally, bluegrass is played on acoustic instruments. Some people will tell you that putting the words “electric” and “bluegrass” in the same sentence creates an oxymoron, like “baroque jazz.” Although those purists have a valid point, electric bluegrass and newgrass are accepted genres that take influence from the early pickers and apply it to more modern instrumentation. And that’s exactly what we’ll do right now.This lesson will focus on the fundamental techniques and note choices you’ll need to unlock the essence of flatpick guitar. Once you digest the basics, you’ll be ready to steal endless amounts of vocabulary from the masters of the style. The first thing to discuss is alternate-picking technique. Traditional flatpickers exist in a purely acoustic world, and being heard over loud banjos, Dobros, and fiddles is extremely important. The best way to achieve this is with a strong picking hand that’s capable of projecting each note to the audience.Ex. 1 is a simple ascending and descending G major pentatonic scale (G–A–B–D–E). This is played with strict alternate picking: Begin with a downstroke, then follow it with an upstroke, then play a downstroke, and so on.The problem with alternate picking will always be when you cross strings. (Note: Entire books have been devoted to this subject—we’re just scratching the surface here.) The two aspects we’ll examine right now are “inside” and “outside” picking.Outside picking is what happens when you pick a string, and then while targeting the next one, you jump over it and swing back to pick it. The flatpick attacks the outside edges of the two strings.In Ex. 2, play the A string with a downstroke, then the D string with an upstroke. This is outside motion. Each subsequent string crossing motion uses this outside picking technique.Most players find the outside mechanics easier than the more restrictive inside motion. As you may be able to work out, inside picking technique is where your pick is stuck between two strings.The following lick (Ex. 3) uses only this inside motion. Play it slowly and then compare how fast and accurately you can play it relative to Ex. 2.You won’t have the luxury of structuring all your phrases to eliminate one motion or the other, so it’s best to accept this reality and develop the skills needed to get by with both approaches. The best of the best didn’t make excuses, they just played down-up-down-up over and over for decades.Ex. 4 features one note per string. This fast string-crossing motion requires a good level of proficiency with both inside and outside approaches to build up any sort of speed.The secret to alternate picking isn’t to always alternate pickstrokes between notes, but to keep the motion of the hand going. In short, the hand will move in the alternating fashion whether or not you strike a string. If you have a stream of eighth-notes, they’ll be alternate picked, but if there are some quarter-notes thrown in, the hand won’t freeze and wait for the next note. You’ll play the note with a downstroke, move up and not play anything, then drop back onto the strings and play the next note with a downstroke (Ex. 5).This way all your downbeats are played with downstrokes and upbeats are upstrokes. You’ll see people refer to this as “strict alternate picking.” With that out of the way, it’s worth looking at the note choices of a typical bluegrass player.A quick analysis of some bluegrass tunes will reveal this isn’t harmonically complex music. Nearly all of the chords you’re going to be dealing with are major and minor triads, so note choice isn’t going to break the brain.One approach would be to play a line based on the major scale of the key you’re in. For example, if you’re playing a song in G, the G major scale (G–A–B–C–D–E–F#) makes a good starting point.A more stylistically appropriate approach would be to use the “country scale,” which is a major pentatonic scale with an added b3. In G that would be G–A–Bb–B–D–E. Ex. 6 shows this scale played beginning in the open position and moving up on the 3rd string.Let’s put all this into practice. Ex. 7 shows a line built around a G chord using this strict alternate-picking motion applied to string crossing mechanics in both directions. This sticks closely to the country scale, but there’s also an added C in the third measure to allow the 3 to land on the downbeat of measure four.This next line (Ex. 8) uses the same idea, but now beginning up at the 5th fret area and moving down over the course of the lick.It’s worth looking at each string crossing to categorize it as inside or outside. This will help further your understanding of the importance of these two picking techniques.Here’s another idea around G (Ex. 9), but to create some smoother motion, this time we add notes from G Mixolydian (G–A–B–C–D–E–F), as well as a bluesy Db (b5) as a chromatic passing tone. The trick here is nailing all the position shifts as you’re going from the 3rd fret up to the 10th fret.Our final example (Ex. 10) takes what we’ve learned about approaching a major chord and applies it to two different chords. First, we have two measures of G, then C, and back to G.When playing over the C, your note choice changes to the country scale, but now built from C (C–D–Eb–E–G–A). Switching between these chords poses a technical challenge, along with a visual one. Take your time with a lick like this, and make sure you’re able to see the underlying chord at all times.

Read more »

How to Play Slower

If you’re a shredder who’s into Yngwie Malmsteen, you probably think Eric Clapton is the slow player. If you love Clapton’s lightning-fast performance of “Crossroads” from Wheels of Fire, you might believe Robert Johnson’s original version (properly titled “Cross Road Blues”) crawls along a little faster than a hyper turtle. And if you can’t wrap your mind around Johnson’s dexterity with the slide, perhaps Brij Bhushan Kabra’s meditative Indian slide playing on Call of the Valley is more your … speed. And, at the risk of waxing philosophical, consider that an open 5th-string A vibrates at 110 Hz a second. Well, that’s still pretty fast by almost any standard! In this lesson we’ll keep in mind (with all due respect to Einstein) this relativity, and approach “slower” from a variety of angles.Sustain Besides resting (which we’ll get to soon enough), the slowest and most engaging way to play a note is to sustain it. There are few more skilled at this than Carlos Santana. On his live version of “Europa” from Viva Santana, Carlos manages to sustain a note for just under one minute (check out the video below starting at 3:36). And though it’s true that the band is playing an upbeat Latin groove over a two-chord vamp, it’s Carlos’ painstakingly sustained note that creates the tension and sense of excitement. Ex. 1 is a Santana-esque groove featuring several sustained notes, including one long-held bend.Ex. 1Europa – Viva Santana version!While Santana proves that you can do a lot with just one note, there are plenty of multiple-note variations you can create from a sustained, vibrating string. When it comes to this approach, one immediately thinks of Jimi Hendrix and his live performances of “Machine Gun,” “Wild Thing,” and “The Star-Spangled Banner.” My favorite Hendrix sustained note can be heard on his version of “Auld Lang Syne” from Live at the Fillmore East, which he recorded on New Year’s Eve of 1969. In this stellar performance, Jimi sustains a note for more than 10 seconds then proceeds to perform the melody without ever picking the strings, using only his whammy bar and a series of slides. Ex. 2 is an imitation of Jimi’s performance using hammer-ons and pull-offs instead of whammy bar technique.Ex. 2In the aforementioned songs, both Santana and Hendrix would have been playing through amplifiers with the volumes completely cranked. While this approach is fun, today you have several options when it comes to performing such long, sustained notes. Countless compressors, actual “sustain” pedals, and digital modeling amps will allow you to play with minimal volume and still achieve infinite sustain. Experiment with different setups to decide what is best for you in any given situation.SpaceA second approach to playing slower, and one that can be achieved with or without amplifiers, is the simple act of resting between phrases, or more dramatically, between the notes that make up your phrases. Now I say “simple,” but if you were to listen to any number of guitar recordings you might wonder, “If it’s so simple, how come so few do it?” It is true, guitar players do seem to have an aversion to resting and creating space in their playing. Still, whether this is out of habit, imitation, or thoughtlessness, the solution is simple.To get comfortable with this approach, listen and imitate vocalists who, unlike guitarists, have to breathe between phrases. A good place to start with vocal mimicry is the study of any number of versions of W.C. Handy’s “St. Louis Blues,” a standard 12-bar form that features a more lyrical and less lick-based melody. Bessie Smith, Billie Holiday, and Etta James all have recorded versions of this blues standard and, notably, Etta’s version begins with a bold a cappella introduction that all musicians could stand to learn from.Ex. 3 features acoustic and electric versions of two choruses of “St. Louis Blues.” The first time through the melody is performed almost identically to the original 1914 sheet music. While this version does have a fair amount of space, the phrasing is rather dull rhythmically. The second chorus adds even more space (resist the temptation to fill the six beats rests at the end of each phrase), is more syncopated, and breaks up each individual lyrical sentence with rests in between words, rather than stringing the lyrics together in one long phrase.Ex. 3There, are of course, myriad other paradigms of vocal phrasing that highlight the use of space and that also translate well to the guitar. Ex. 4 borrows heavily from Patsy Cline, who was particularly adept in her use of space and timing, often pausing unexpectedly and then twisting her notes into a surprising series of syncopations that few other musicians would have considered. It starts with a very straight, Fake Book-style delivery, then reveals how Patsy might vary a repeated phrase with her use of space, articulation, and rhythmic variation, similar to the verses of “Crazy.”Ex. 4RefinementOne of the numerous benefits of playing slower is that it can underscore the subtler aspects of one’s guitar technique. By performing an attack or articulation gingerly, the art can be heard in both the procedure and the musical result. Jeff Beck is a master of this type of slow playing, and his 1976 recording of Charles Mingus’ “Goodbye Pork Pie Hat” is the archetype performance. Ex. 5 takes many of the slow articulations Beck uses in “Goodbye Pork Pie Hat”—measured bends, circumspect slides, deliberate rakes, even the elusive click of switching pickups—and applies them to “Amazing Grace,” which Beck has also recorded, though with a different approach and, ironically a, slightly faster tempo than presented here.Ex. 5SoloLegions of fingerstyle guitarists are under the impression that, because they’re playing solo, they must play all the usual parts at once and it must be rhythmically relentless. As a result, far too much fingerstyle music is one-dimensional. Not so for Leo Kottke’s music. Though Kottke is notorious for playing more notes in one song than most guitarists perform in 10, he also has pieces that he delivers with a leisurely approach: “Three Walls and Bars,” “Parade,” and “Easter” are all prime examples. Ex. 6 is an homage to Kottke’s more relaxed compositions. It features an amalgamation of the aforementioned songs, plus a little Robbie Basho thrown in too.Ex. 6Listen Superficially, this final approach to slowness might seem radically different from all the previous examples, but in fact, incorporating this exercise into your regular practice routine can make everything you play, slow or fast, take on new levels of meaning and purpose.Now many of you might think this technique is little more than new-age hokum, and I can appreciate that. Still, there is no agenda here other than to help you become a more thoughtful and musical player, so I entreat you to give this next exercise a few tries to see if it enhances your playing. If not, you have the six previous examples to work with. But if it does, it could change your playing forever. (Note: I have only reluctantly included an audio version of this exercise because I feel it does not translate well to any recorded audio medium. The true test is the sound you yourself create. If you do use my audio as a guide, please listen with headphones.)Rather than attempting to explain—acoustically, mentally, and physics-wise—what is going on when you perform this exercise, I urge you to simply follow the instructions below. After experiencing the sounds, you can decide if you’ve begun listening and hearing differently. (Note: This exercise is best done with an acoustic guitar or with an electric through a relatively clean, low-volume amplifier, otherwise you might be sustaining and resting for much, much longer than you want to.)1) Find a relatively quiet room in which to do this exercise.2) With your eyes closed, pick one note.3) Let it sustain as long as it will naturally, with no vibrato.4) When the note has decayed fully, take your hand off the guitar and rest for approximately the same amount of time that the note sustained.5) Repeat this exercise, at least three more times, with any notes you choose.6) Evaluate the process.What did you hear? If you’re like many players I’ve done this exercise (Ex. 7) with, you may have noticed more than you would have imagined. For instance, you can actually hear the overtones. Overtones are another topic beyond this scope of this lesson, but the briefest of explanations is to say that there are no “pure” notes in music. Every note is made up of several discrete frequencies, the fundamental (the name we give the note) and many overtones (additional frequencies greater than the fundamental), which usually go undetected if one doesn’t play slowly. By playing at this glacial pace, one can hear notes within notes.premierguitar · How to Play Slow Ex. 7Your instrument sustains for much longer than you thought possible.Different attacks create tones. Did the exercise encourage you to modify your attack? Perhaps you tried using your bare fingers instead of the pick? Did you find yourself picking harder or lighter? Did you pick in different areas relative to the acoustic’s soundhole or the electric’s bridge?Resting between notes makes each subsequent note sound fuller.The lower the note, the longer the sustain.Does noticing these small details make you a better player? That is not for me to say unequivocally, but certainly this exercise in active listening allows one to recognize the strongest aspects of one’s playing and to rectify the weaker aspects. It also can give musicians a greater appreciation of numerous facets of sound, from sound waves and frequency vibrations to one’s own auditory perception. If this exercise and these topics are of interest to you, I suggest following up with an investigation of the works of John Cage, Pauline Oliveros, and La Monte Young, as they have all worked seriously within the realms of silence, long sustained notes, and what Oliveros calls “Deep Listening.”Less is More, When There’s MoreAs so often is the case, balance is crucial. Musical choices don’t have to be autocratic, dogmatic, or absolute. Slow playing is highly effective when it’s offset by its counterpoint—speed. While practicing, if you forgo automatic pilot and remember to equalize a barrage of notes with rests, or long, sustained notes, or pithy, quarter-note phrases (as opposed to 32nd-note run-on sentences), when it comes time to perform, your playing will be invigorated by complementary and dynamic ideas. And, paradoxically, playing slower will make your fast playing seem even faster.

Read more »

Beyond Blues: Nail Those Changes!

It’s easy to just live inside a single pentatonic or blues scale over an entire 12-bar progression, but how hip is it when you hear players really get inside those chord changes? In this lesson we’ll explore some simple techniques that will allow you to create solos that lead the ear through the progression. The goal? To be able to take a cohesive solo that outlines the changes without another instrument providing the harmonic foundation.Now, we aren’t immediately jumping into Joe Pass territory here. I want to share some techniques to build your confidence, so let’s start with just two notes to demonstrate how easy it is to outline the sound of a chord.As promised, Ex. 1 only deals with two notes—the 3 and the 7 of each chord. For all our solos, we’ll use a guitar-friendly 12-bar blues progression in the key of G. The first step it to outline the target notes for each chord. Because these are all dominant 7 chords—which have a formula of 1–3–5–b7—we’ll lower the 7 by a half-step:G7 – B and FC7 – E and BbD7 – F# and CI set up the notes so they connect to the next chord by either a whole- or a half-step. A good general rule for voice-leading is “Leap within and step across.” This means that it’s cool to hop around when playing through a single chord, but when you want to connect to the next chord, keep the movement small.Ex. 1 We’ll add the root into the mix for our next solo (Ex. 2). You can see how we’re now building on the previous example by adding more color to the canvas. I should also mention that my 16th-notes have a swing feel. This adds some bounce. I’m also doing some large interval leaping within the chord changes, which creates a cool call-and-response effect.Ex. 2 You might be able to guess what’s next. Yes—it’s time to add the 5 of each chord to our pool of options. Now we have the full four-note arpeggio available to us:G7: G–B–D–FC7: C–E–G–BbD7: D–F#–A–CI don’t treat these arpeggios as linear phrases. I know that these notes make up the sound of each chord, but I also know that I don’t have to play them in order. The trick is to come up with interesting riffs or lines and then connect those ideas across the chord changes (Ex. 3). I’m afraid I have to add a disclaimer for this example: In measures four and eight I use an F# as a passing note in my line over the G7 chord. I was caught up in the moment!Ex. 3 In Ex. 4, we expand our note choices to include the 6, or 13. Since we’re dealing with dominant chords, which contain a b7, I prefer to call them 13. But that’s just theory mumbo-jumbo. [Editor’s note: When constructing chords that use tones other than the 1, 3, 5, and 7 of a standard “7th chord,” the color note in question can occur in the same octave as the root, or an octave above the root. The latter are technically termed “extended chords” because they reach beyond the 7 into the next octave. These include 9, 11, and 13 chords that can be major, minor, or dominant, depending on what type of 3 and 7 they contain. Just remember this: Whenever you see a number greater than 7, simply subtract 7 from it and you’ll get the scale degree in the same octave as the root. That’s the color note you’re dealing with. In this case, 13 – 7 = 6. So in the chord spelling below, this note appears as the 6, even though you might actually play it an octave higher than the root as a 13.]Here’s what we have now:G7: G–B–D–E–FC7: C–E–G–A–BbD7: D–F#–A–B–CHere we break the rule of leaping within the chord and stepping across from one to another. The riff here is being used as a sequence, and I superimpose almost the exact same phrase on all the chord changes. You’ll notice you’re jumping around the neck playing almost the identical fingering on each chord change. In harmony, sequential motion takes precedence over normal voice-leading rules.Ex. 4 Next up, we add the 9 to each chord. [Remember our “subtract 7” formula: 9 – 7 = 2. So in the chord spellings below, the color note in question is shown as a 2, though you’ll often play it an octave higher as a 9. Same scale tone, different octave.] This is a common note to add to not only dominant chords, but major and minor chords, too. Here’s where we’re at:G7: G–A–B–D–E–FC7: C–D–E–G–A–BbD7: D–E–F#–A–B–CIn Ex. 5, I combine sequential and non-sequential approaches. In measure two, you’ll hear I reference what I played in Ex. 1. Leading into measure one you’ll notice that I use the note A#, which is one half-step below the chord tone B. This is a typical musical expression used in blues and many other styles of music. I just think of it as sliding into the first note I’m going to play. I wouldn’t over-analyze it—this is just a quick approach note. The last three measures of this demonstration are a great example of leaping within a chord and moving by step into the next chord change.Ex. 5 Our final piece of the puzzle is to add the 11, or 4, to the mix. [Once again, our “subtract 7” formula comes into play: 11 – 7 = 4.] We now have progressed from the bare-bones guide tones—3 and b7—all the way through arpeggios and landed on the full Mixolydian mode for each chord.G7: G–A–B–C–D–E–FC7: C–D–E–F–G–A–BbD7: D–E–F#–G–A–B–CThe interesting thing about this step-by-step method of discovery is that you get to hear how each of the scale tones fit over the dominant 7 chord. You’ve learned how they function—not just their names. This is a big step in understanding and hearing what you are playing. In Ex. 6, I go all-out on one sequence that I try to weave through all the chord changes. The rhythm is a little tricky, so I would suggest that you memorize the sound of the example and be able to sing it. If you can sing it, you can play it!Ex. 6 In closing, I want to leave you with a thought about the rhythms I used throughout the examples. A good sense of rhythm and a depth of rhythmic ideas are as essential to great soloing as your harmonic chops. Rhythm and harmony are equal partners. Make sure you work on both!

Read more »

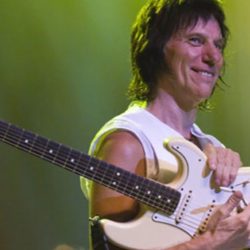

The Tao of Jeff Beck

Jeff Beck is arguably the most eclectic and ever-evolving guitar hero. He was part of the holy trinity of Yardbirds guitarists, along with Eric Clapton and Jimmy Page, and is the one who has consistently remained at the forefront of the electric guitar ever since. From John McLaughlin to Eddie Van Halen, Beck is a favorite of just about any guitar player you could name, and that includes the other Yardbirds alumni. Stephen Colbert explained it best at the Grammy awards, “You know the game Guitar Hero? He has the all-time high score—and he’s never played it.” Let’s take a look at some of the many highlights of Beck’s playing throughout his illustrious and uncompromising career.Beck’s stint with the Yardbirds—including his groundbreaking work on such psychedelic hits as “Over Under Sideways Down” and “Heart Full of Soul”—cemented his iconic status, but his melding of influences from Chuck Berry, Cliff Gallup, and Les Paul on the blues instrumental “Jeff’s Boogie” was eye-opening to legions of guitarists in the wake of the British Invasion. Here’s a Cliff Gallop-inspired rockabilly phrase (Ex. 1) that uses pull-offs for speed.Ex. 1 The chromatically climbing lick in Ex. 2 reveals Beck’s brilliant technique and his love of flashy and dramatic fretwork.Ex. 2 Like Clapton and Page, Beck was steeped in Chicago blues, and as with those players, he developed a distinctive voice in the style early on. This Truth-inspired solo (Ex. 3) on a 12-bar blues demonstrates some unison bends (measures 1–4), ostinato licks (measures 5–8) and a quirky, pre-bend idea in the final section.Ex. 3 When Jeff Beck Group was released in 1972, it offered a premonition of Beck’s unique approach to the tremolo bar that would become so important to his playing in the decades to come. In Ex. 4, a wild use of the bar gives a modern and innovative twist to what could otherwise be more conventional blues ideas.Ex. 4 Our next phrase (Ex. 5) is in the spirit of “Freeway Jam” and a host of other funky instrumentals from the 1970s, and it showcases Beck’s use of the Mixolydian mode (1–2–3–4–5–6–b7). With its major quality and lowered 7, this scale is tailor-made for playing over dominant 7 and 9 chords. Beck often uses it as the basis for both melodic themes and improvised solos. Frequently, he further embellishes Mixolydian lines with bluesy ideas, like the Bb (b3) to B (3) leading into the final measure.Ex. 5 Beck’s impressive ballad work, inspired by the great Roy Buchanan, is heard on the classic Stevie Wonder composition, “’Cause We’ve Ended as Lovers.” In Ex. 6 you’ll hear many C minor pentatonic (C–Eb–F–G–Bb) licks with a host of bending techniques, such as compound bends (measure 2) and pre-bends (measures 3 and 7). Virtuosic ostinato–based figures are used to great dramatic effect in measures 5 and 6.Ex. 6 Beck’s revival of “People Get Ready” was a career high point in the late ’80s, and it made a clear statement of his relevance as one of the most expressive and distinctive guitarists of the day, already more than 20 years into his career. Bending finesse, with fingers and tremolo bar, and even a simple taste of a finger tap is present in Ex. 7. This is perhaps the clearest example of the precise tremolo bar usage to come, and worth mastering before tackling the likes of “Where Were You” or “Over the Rainbow.”Ex. 7 Our final example (Ex. 8) is a phrase from the Bulgarian folksong “Kalimanku Denku.” This particular vocal music is perfect for working on Beck’s tremolo stylings because it is, in fact, what inspired much of his playing in the past 20 years. Check out a compilation album called Le Mystère des Voix Bulgares to hear what Beck used as the model for his mature and advanced tremolo bar work. Also, make sure that you adjust your tremolo to float, i.e., so that it can raise a note by a minor third on the 3rd string. To check, play an open G note and be able to bring it up to a Bb.Ex. 8

Read more »

One Note at a Time: A Chet Atkins Primer

As inspiring as it is to hear Chet Atkins play some mind-bending fingerstyle licks, it can be quite daunting to decode what he’s doing. Where do all those sounds come from? How do we create our own tunes or arrangements in that style?It’s useful to break a big job down into smaller parts, and “Chet-style guitar” certainly benefits from that approach. We’ll break this technique down to the smallest components; once we understand the elements, we’ll then be able to build up arrangements using this knowledge. Practicing this way helps beginners form good habits, and it also gives experienced players a chance to identify and fix bad habits that are often the result of ineffective practice.Gaining independence between the picking-hand thumb and fingers is the foundation of all Chet-style playing, and we’ll be focusing on this foundational aspect most of all in this lesson. Because this style often involves moving shapes and bass lines, a few fretting-hand fingering suggestions are provided next to the noteheads in the standard notation clef. If you’re a tab reader, feel free to just glance at the standard staff for fingering suggestions if a passage is feeling clumsy or you feel the need for some guidance.Here’s a tip: For authentic tone, place the back of your picking-hand palm just behind the bridge to mute the bass strings. This will serve you well as you begin to develop a strong groove with your thumb.Although the alternating bass that’s characteristic of Chet’s playing owes much more to Merle Travis than Blind Blake, country-blues players would often drone one bass string below a melody played on the treble strings, as in Ex. 1. This “steady thumb” blues approach is a great way to learn how to keep rock-solid time with that digit. In his formative years, Chet heard a lot of different kinds of music, including pre-war blues. With the quarter-note bass, be sure to practice with a metronome to internalize a good sense of time, and ultimately, groove.Ex. 1 After establishing the bass, add in melody notes. If a measure is challenging, even a single example can be broken down into smaller parts. Think of each measure in Ex. 1 as a separate exercise. It takes a lot of practice to reach your goals with the guitar, but effective practicing is the fastest and most direct route. Practice each example, or even each measure, until it comes naturally. Be sure to make a distinction between a slow performance tempo and a slow practice tempo. There is no such thing as practicing too slowly.Of course, it doesn’t really sound like Chet until an alternating bass is introduced, so let’s move onto a more typical Chet-style phrase in Ex. 2. Start out by simply getting used to the bass pattern in measures one and two, and then add some melody notes to the open chord shapes. By keeping the fretting hand simple, we place all our attention on forming a good groove with the picking hand.Ex. 2 Now that we have a foundation, it’s time to start syncopating the melody, as shown in Ex. 3. The combination of alternating bass and syncopation in the melody gives the example more of a Chet-approved feel. It’s here we begin to dig into the finer details of his playing.Ex. 3 One such detail is learning to alternate between not just two, but three notes in the bass. Some of Chet’s arrangements contain sections that move between a two-note bass pattern and a three-note bass pattern (check out “Ain’t Misbehavin’” from his 1957 release, Hi-Fi in Focus.) The three-note pattern sounds fuller and relies on having an open string available that matches the chord tone, or an extra finger free in fretted shapes. In Ex. 4 we’ll keep it simple with open shapes in the key of A and familiarize ourselves with the pattern in measures one and two.Practice alternating the 5–4–6–4 string pattern. That will form the foundation of the house. After adding in some melody notes in measures three and four, we’ll switch to the IV chord, but this time inverting it so that the F# is in the bass. This allows us to use a new string pattern: 6–4–5–4. Those two patterns will cover 99 percent of Chet’s thumbpicking tunes.Ex. 4 Mark Knopfler & Chet Atkins – Instrumental MedleyMark Knopfler was one of Chet’s biggest fans and the duo released Neck and Neck in 1990 to critical acclaim. Here’s a performance from The Secret Policeman’s Ball in 1987 where the pair play “I’ll See You in My Dreams” and John Lennon’s “Imagine.”Once the new alternating patterns are in place, add some syncopation (Ex. 5). In measure five, you’ll have to either stretch your fourth finger to reach the G# on the 1st string, or shift positions. Fingerstyle guitar is great for exercising the often-neglected fourth finger, but be careful not to overstretch or strain your fingers. If something is uncomfortable, stop and find a new position to play it in. Where there’s a will, there’s a way.Ex. 5 Now that we’ve established a solid foundation for the thumb patterns and a good groove, it’s time to combine moving chord shapes up and down the neck with everything we’ve practiced so far. These new shapes facilitate another characteristic aspect of the Atkins style: open strings ringing against a fretted note on the adjacent string, as in Ex. 6. The example ends with a textbook Chet voicing of the A6 chord, which continues the theme of playing fretted notes against the open 1st string. Ex. 6 When it comes to melodies, so much of the movement in fingerstyle guitar involves finding the best placement of the melody to fit comfortably within a given chord shape. Chet’s hands never moved more than necessary, and as gifted as he was, part of his genius was a masterful economy of motion. One effective way to move around the neck and accommodate a shifting melody is to slide your hand down to the target pitch. In measure one of Ex. 7, for instance, notice how I slide from C# down to A to shift positions. In the next measure, I use a bass line to move up into 10th position for the IV chord. Although the melodies and tunes vary, the approaches and techniques recur time and time again. Ex. 7 In a 4/4 fingerpicking groove, very often either the 2nd or 4th beat (or sometimes both) will involve a bit of a strum. Chet’s thumbpick would drag onto the 3rd string so that the muted bass was heard in conjunction with the clarity of an open string or fretted note. Often this blended into the total picture he was painting, and on his classic recordings with drums and bass, this can almost be lost to the ears, but it is an important part of the finer details. Simply listening to a lot of old Chet Atkins recordings is the best way to internalize this sound and feel, but like anything, eventually it needs to become personalized via practice. In Ex. 8 we move the sound from our ears into our hands. Try to place the strum exactly where indicated in the notation to get used to adding this detail into the mix. In the long run, you’ll find it becoming entirely natural and a bit arbitrary exactly where—or even if—you want to strum. The technique becomes more of a mindset than a literal move to perform the same way every time. Have fun with it and remember that Chet never played anything exactly the same way twice. This example concludes with a classic Chet-style single-note lick that features fretted pitches alternating with a recurring 3rd-string drone.Ex. 8 As a great admirer of Johnny Smith and many other jazz guitarists, Chet was always expanding his vocabulary of chords and harmony. Learning chord inversions is essential to incorporating both harmony and melody in your arrangements. Early on, Chet’s inversions owed much more to Merle Travis than Lenny Breau, but he never stopped expanding.In Ex. 9 we look at a classic Chet inversion of a D7 chord, placing the F# (3) on the 6th string, with the b7 on the 5th string at the 3rd fret. To make this shape, the left-hand thumb wraps around the neck to grab the low F#, leaving the remaining fingers free to fret the other pitches. An open 1st string sounds great against this shape and is a frequent melody note when Chet uses this inversion. Continuing onward with the left-hand thumb, the G/B on beat 3 of measure three creates a nice ascending bass line on the way to the IV chord (C). We then descend through the G/B again on the way to a D9 shape that places the A note in the bass on beat 1. This gives us a bass line that both ascends and descends. This isn’t merely effective hand positioning, but also musical voice leading and bass motion.Ex. 9 With all the pieces of the puzzle now coming together, let’s combine every concept we’ve worked on in Ex. 10. Although it seems like a lot to keep track of, anyone can play anything if it is slow and isolated enough. Whether you’re just starting out or a seasoned pro, remember that the big picture is composed of effective, tiny steps. Take as much time as you need to master each component—no one has ever been able to learn it all within a life and Chet never stopped learning either. Approaching the guitar one note at a time is the surest way forward.

Read more »