This post was originally published on this site

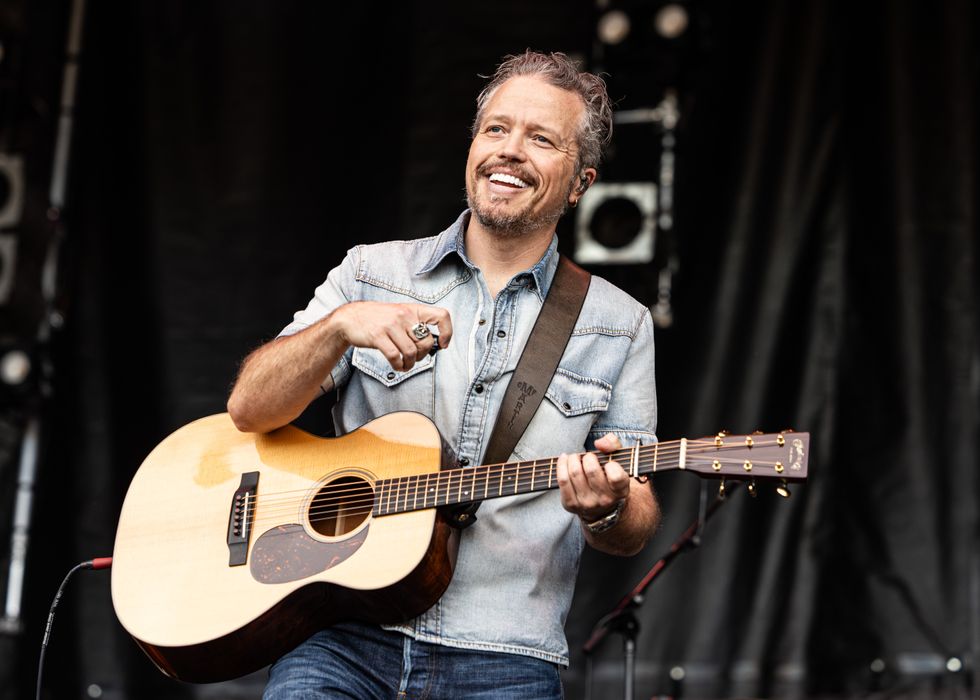

Imagine, just for a moment, that you’re a successful, internationally recognized singer, songwriter, and guitarist. (Nice dream, right?) You’ve been in the public eye nearly a quarter-century, and for all that time you’ve either been a band member or a band leader. Then one day you decide the time is right to step out on your own, for real. You write a bunch of new songs with the express intent of recording them solo—one voice and one acoustic guitar, performed simultaneously—and releasing the best of those recordings as your next album. No overdubs. No hiding behind other musicians. No hiding behind technology. For the first time, it’s all you and only you.

Would you be excited? Would you be petrified?

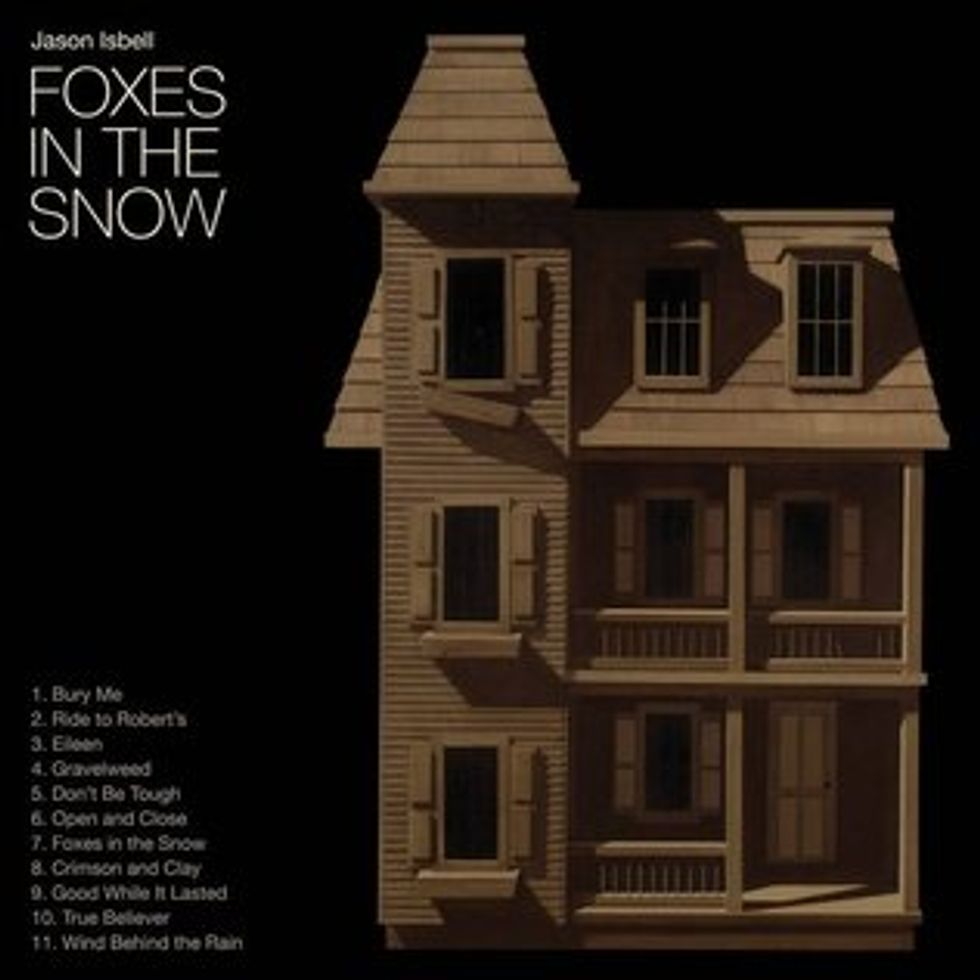

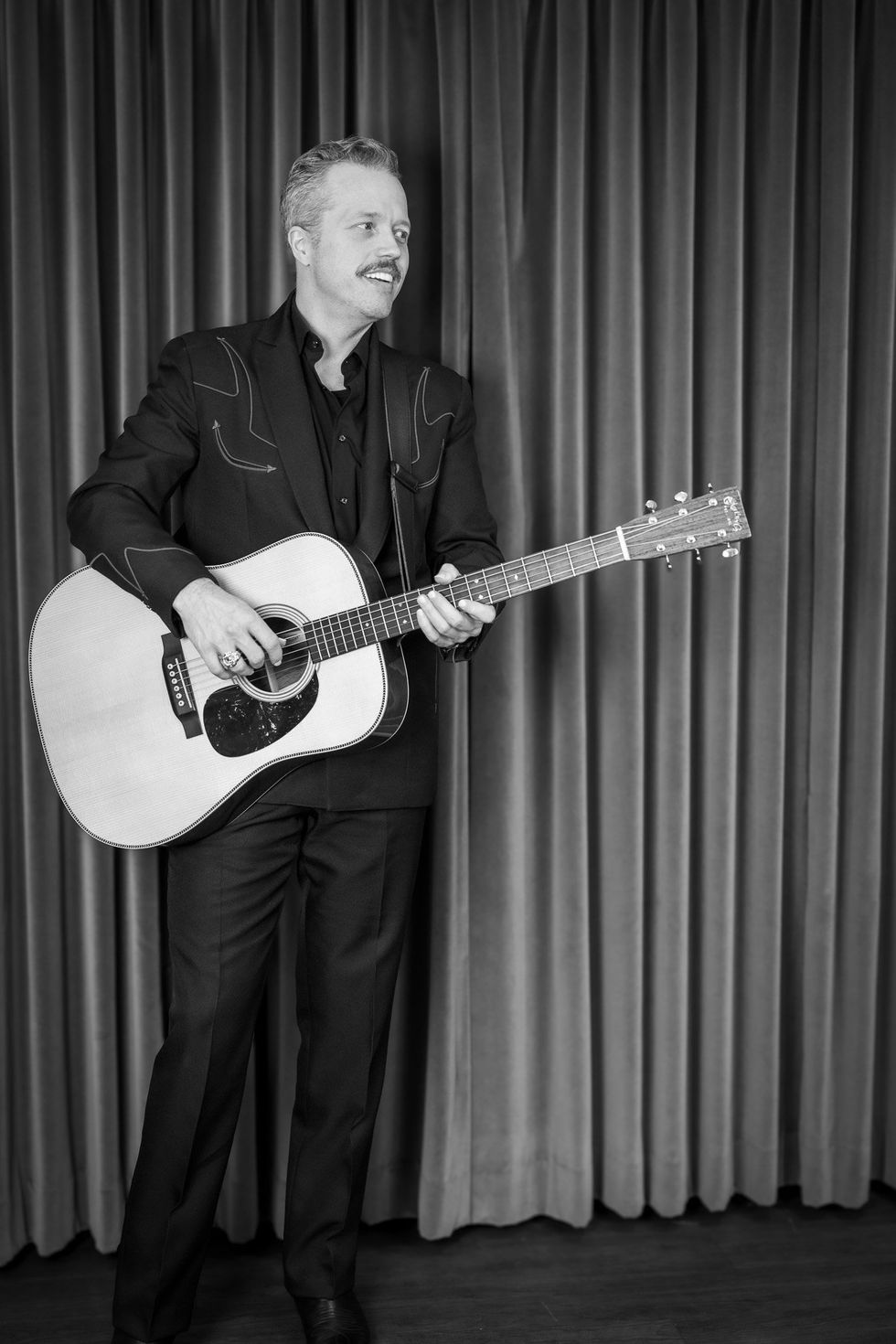

This is the challenge that Jason Isbell voluntarily took on for his 10th and latest album, Foxes in the Snow. There were some extenuating circumstances. He was sorting through the aftermath of a very public breakup with his longtime partner in life and music, singer/violinist Amanda Shires, and the new songs reflected that situation, sometimes uncomfortably. Music this personal needed a personal approach. And so, when Isbell entered Electric Lady Studios in New York City for five days of recording last October, none of the members of his regular band the 400 Unit were there. He was accompanied only by co-producer/engineer Gena Johnson, who’s worked with him regularly for the past eight years.

Soundstream

“It was difficult to pull off,” Isbell acknowledges via Zoom from his Nashville homebase, “but it didn’t require me to look for ways to make the record sound weird. And that’s important to me, because what I don’t want to do is write a bunch of songs and then go in the studio and intentionally try to make them sound strange, just so they don’t sound like things I’ve done in the past. It made sense to me to just walk into a studio with a guitar and a notebook and make a record that way. First of all, because I can, and I’m grateful for the fact that I can. And I also thought that it would be really hard. And it was.”

Making it especially hard was Isbell’s insistence on not overdubbing his vocals. “I didn’t want [the album] to sound like anything that could have been replicated or fabricated,” he explains. “I wanted it to sound like somebody playing a guitar and singing. To me, the only way to do that was just to go in there, sit down, and play it. And it’s hard to play the guitar and sing at the same time in the studio. Normally, that’s something you wouldn’t do; you’d be in a really controlled environment with mics on the guitar, everything would be isolated, and you’d have to play very carefully, not the way you play live. The idea of doing that while singing master vocal takes … well, it was tough, because if you screw up, well, you just screwed up. But the good news is you don’t have to make everybody else start over, and I liked that. I liked the fact that if I messed up, I could just stop and immediately try another take.”

“I brought an old D-18 into the studio, like a ’36 or ’37, and it sounded beautiful, but it didn’t sit in the right spot. It ate up so much space, and it was so big.”

Being aware of the difficulties and doing it anyway—that can’t help but be a vote of confidence in one’s own ability as a musician. And it should come as no great surprise that Isbell’s confidence was well-founded. Foxes in the Snow shines a bright spotlight on his guitar playing, and the playing proves eminently worthy of such a showcase. From the bluegrass-tinged solo on “Bury Me” to the Richard Thompson-esque fingerpicking at the end of “Ride to Robert’s” and the bouncy, almost Irish-reel-like hook of “Open and Close,” Isbell always gets the job done, coming up with tasty parts and executing them with panache. It’s been easy to forget in recent years amid all the critical accolades and Grammy wins that when Drive-By Truckers brought Isbell into their fold in 2001—his first major-league gig—they didn’t do it because of his singing or songwriting, which were still unknown quantities at the time; they did it because of his considerable skills as a guitarist. By putting those skills on display, Foxes in the Snow helps rebalance the Isbell equation.

Jason Isbell’s Gear

Acoustic Guitars

- 1940 Martin 0-17

- Martin Custom Shop 000-18 1937

- Two Martin OM-28 Modern Deluxes

- Martin D-35

- 1940s Gibson J-45

- Fishman Aura pickup systems

Electric Guitars

- 1959 Gibson Les Paul

- 1961 Gibson ES-335

- Various Fender Telecasters and Stratocasters

Amps

- 1964 Fender Vibroverb

- Dumble Overdrive Special

- Tweed Fender Twin

Strings, Picks, & Capos

- Martin Marquis phosphor bronze acoustic lights (.012–.054)

- Ernie Ball Regular Slinkys (.010–.046)

- Dunlop Tortex 1.14 mm picks

- McKinney-Elliott capos

And it does so while employing one guitar and one guitar only: an all-mahogany 1940 Martin 0-17, purchased within the past couple of years at Retrofret Vintage Guitars in Brooklyn. “My girlfriend [artist Anna Weyant] lives in New York,” Isbell notes, “and I didn’t want to keep bringing acoustics back and forth. I’ve got a lot of old Martins and Gibsons, and I don’t love to travel with them and subject them to air pressure and humidity changes. So I needed a guitar that could just stay in New York. As far as pre-war Martins go, it’s about the least special model that you could possibly find. But it sat perfectly in the mix. I brought an old D-18 into the studio, like a ’36 or ’37, and it sounded beautiful, but it didn’t sit in the right spot. It ate up so much space, and it was so big. The sonic range of that guitar was overpowering for what I was trying to do, and with the little single-0 I could control where it was in relation to my vocal.”

“There’s Bon Jovi and Bruce Springsteen and Paul McCartney all staring at me, and I knew that I had to sing in front of them with a busted voice.”

That control was important, because Isbell’s voice is spotlighted even more brightly on the new album than his guitar work. If you hear more strength in his singing these days, it’s not your imagination; he hired himself a vocal coach last year—out of necessity. “My voice failed,” he says simply. “I didn’t have any nodules or anything, but for some reason, anything above the middle of my range was gone. It was painful and embarrassing. I was doing the MusiCares tribute to Bon Jovi [in February 2024] and my voice was gone and I knew it. I was singing ‘Wanted Dead or Alive’ on stage, and I looked down and there’s Bon Jovi and Bruce Springsteen and Paul McCartney all staring at me, and I knew that I had to sing in front of them with a busted voice.” He pauses and sighs. The sense of humiliation is palpable.

“You know, I did it,” he continues after a few seconds. “I did my best, and it was not good. And then after that I started working with this coach, and it made a huge difference. I figured out that I hadn’t been singing in a way that was anatomically correct. I’d been squeezing and pushing all these notes out, and [the coach] was good enough to manage to keep my vocal quality the same; I didn’t have to change the way I sounded, I just gained a wider range and a lot more stability. Now I’m able to sing more shows in a row without having vocal trouble. It’s been really, really nice.” He pauses again, this time to laugh. “And I made fun of people for so many years for blowing bubbles and, you know, doing all the lip trills and everything backstage … but here I am doing it myself.”

Isbell’s voice has made gains in both upper and lower range, as the Foxes in the Snow ballad “Eileen” demonstrates. In a clever touch, he pairs an unusually deep vocal part with a high, chimey guitar line, produced by placing a capo on the 0-17’s 5th fret. “Now that I’ve learned how to sing after just hollering for my whole career, I’ve got the ability to support a vocal in that low a key,” he says. “Having a vocal coach made it possible for me to sing a song like that. And the 5th-fret capo is a little tricky sonically, too. People usually go between two and four [the 2nd and 4th frets]. At least I do. Matter of fact, when I was a kid, my grandfather didn’t like for me to capo up over the third fret. I remember he’d tell me that would damage the guitar. I’ve never found a way that it would damage the guitar,” he adds with a grin. “I think it just irritated him.”

“My grandfather didn’t like for me to capo up over the third fret. I remember he’d tell me that would damage the guitar.”

Growing up in northern Alabama in the 1980s, Isbell took to music in large part because of his multi-instrumentalist grandfather. “He was a Pentecostal preacher, and he played every day. When I’d stay over with him, he’d play mandolin or banjo, fiddle sometimes, and I would have to play rhythm guitar. And then my dad’s brother, who’s a lot closer to my age, had a rock band. He taught me to play the electric guitar and rock ’n’ roll songs. I feel like I just got lucky that I loved it so much. That’s really at the heart of it—the fact that I’ve never had to sit down and practice because I just think about it all the time.”

This is not to say that Isbell doesn’t practice; quite the contrary. Indeed, one of the most moving segments of Sam Jones’ excellent 2023 documentary on Isbell for HBO, Running With Our Eyes Closed, is when he recalls just how crucial practicing became to him as a child. The guitar was a refuge, a way to literally drown out his parents’ vicious arguments in the next room. (Another poignant aspect of Jones’ film, shot mostly in 2019 and 2020, is the delicacy with which it captures the often tenuous state of the Isbell/Shires relationship, prefiguring their breakup.)

When asked what exactly it is about the guitar that makes it so special to him, Isbell doesn’t hesitate. “The guitar is the best instrument,” he says. “It’s the smallest, most portable instrument that you can make full chords on. You can’t take a piano to a dinner party, you can’t accompany yourself on a clarinet, and you need something that’s big enough to where the volume of it can fill a room. In the days when everyone had acoustic instruments, like in the 1920s, there was nothing else like the guitar that you could carry on your back and travel from place to place and entertain people with.”

“I realized pretty early on in the solo experiment that when you’re playing with the band, you don’t have a chance to work with tempo or volume in the same way.”

With that question answered, all that remains is to inquire, now that Isbell’s done the solo acoustic thing once—both in the studio for Foxes in the Snow and live for his tour to promote the album—whether he’d ever consider doing it again. “I don’t see why not,” he responds. “It’s not in any kind of plan right now, but I enjoyed the challenge of it. And I think anything that makes me turn off the ‘Don’t fuck this up’ switch is good for me, because if you sit there and spend the whole time thinking, ‘Don’t fuck this up,’ you’re not ever gonna get into that zone where you’re communicating with the work, and you’re not ever gonna get to a point where you can deliver it comfortably. This has been a really good opportunity for me to just practice letting all of that go.

“Obviously I miss the horsepower of the band,” he adds. “I miss the people individually, being on stage and communicating musically with them. But I realized pretty early on in the solo experiment that when you’re playing with the band, you don’t have a chance to work with tempo or volume in the same way. Usually you’re just trying to count a song off at the same tempo you recorded it in or the way you’ve been playing it lately, but when it’s just me, I can intentionally speed up and slow down within a song. And with respect to the volume, I can drop the bottom out soquickly, whereas it’s more like steering a ship when I’ve got the whole band up there—it happens more slowly, no matter how good they are. I would not enjoy this as much if I had to do it all the time,” he concludes. “But it’s nice to have both sides.”

YouTube It

In this version of “Ride to Robert’s,” Jason Isbell demonstrates the flexibility of playing solo by picking up the tempo of this song from Foxes in the Snow.