This post was originally published on this site

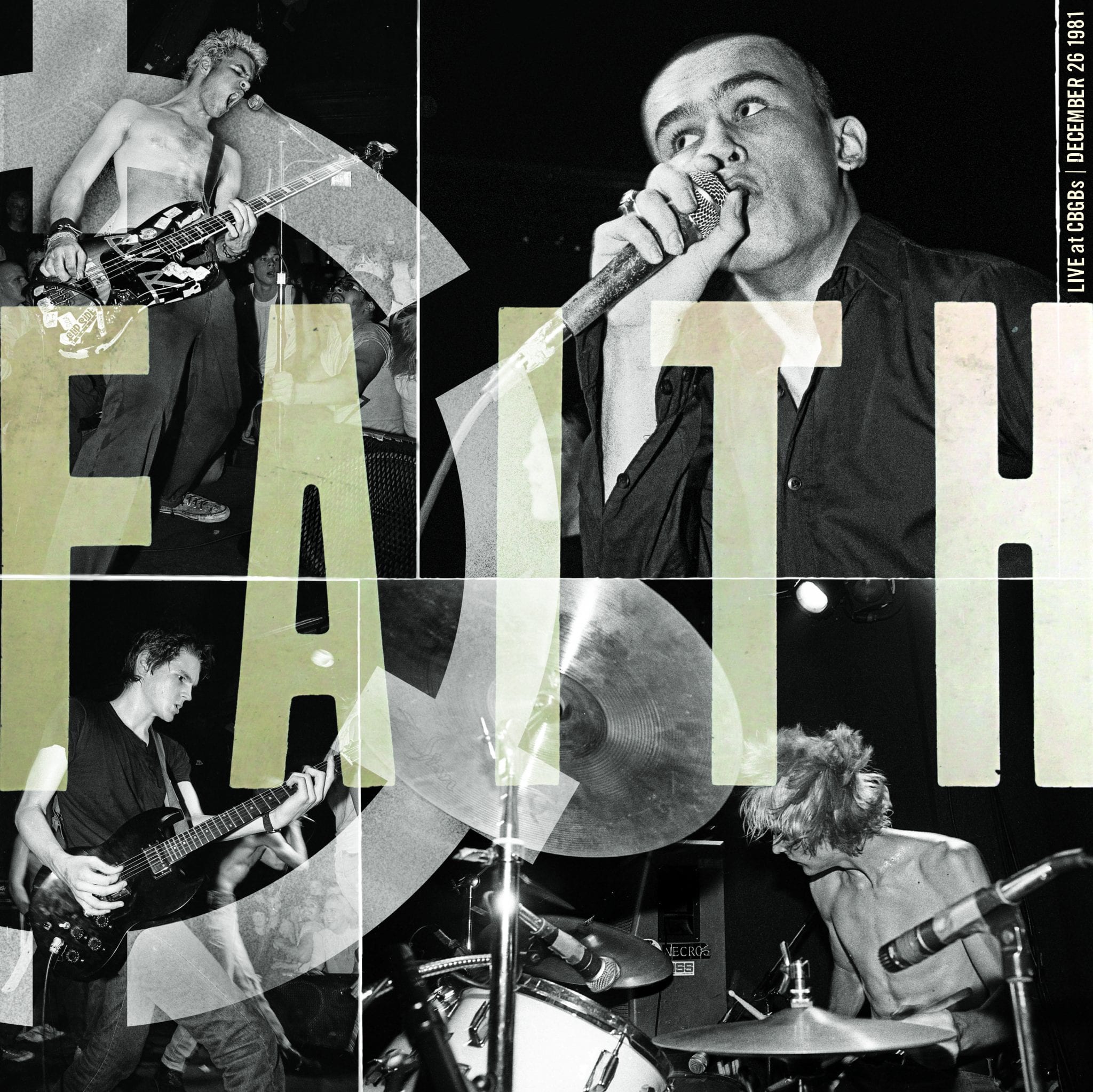

From the wild careening of the songs to the constant serendipity of the shouldn’t-work-out-but-does travel and band “business” described in the rousing, revelatory accompanying liner notes, Live at CBGBs — capturing an absolutely scorching late 1981 set by DC Hardcore game-changers The Faith opening for the Bad Brains — really does feel like a brief in favor of the magic that can happen when one does not place boundaries on oneself; on liberation and art through chaos, essentially.

Ivor Hanson — drummer of The Faith as well as the equally legendary Embrace and author of the acclaimed memoir Life on the Ledge: Reflections of a New York City Window Cleaner — was kind enough to chat with Decibel about the way that show and moment in time continues to reverberate throughout his life — and, in doing in such a thoughtful and incisive way, helps explain why the music and movement he helped create continues to reverberate through ours…

Returning to this nearly forty years later, do you find that freedom and heat inspiring in the context of your current life and the world we’re all attempting to navigate?

“Liberation and art through chaos” describes and frames that show so well. And though not in the same way, I do find that “freedom and heat” inspiring my current life, which, with two kids in hybrid schooling, can easily be described as at least a fair bit chaotic.

I have to say that I find it hard to believe that my daughter, at 15, is just a few years younger than I was at that show, while my son, at 10, is just slightly older than I was when I knew that I wanted — no, needed — to play the drums. And though neither is into punk rock — at least not yet! — I so want them to experience an equivalent “magic” in their lives, with her drawing and his playing the flute. Fingers crossed…

As for me, this past year, I’ve been writing fiction for the first time and am enjoying how serendipity and this-shouldn’t-be-working-but-is are informing the story in terms of details, plot, characters, and such. The difference, of course, is that while I can rework this or that chapter, you can’t do over a live show. Still, the power of that music, that scene, does work for me still. Distorted guitars by Michael (“Don’t Tell Me”), or Dr. Know (“Big Take Over”) — or, for matter, Paul Fox of The Ruts (“S.U.S.”) — will always put me in the mindset to do anything I set my mind to.

As for navigating the world as it currently is, the pandemic has thrown up so many boundaries — Zooming school and work; masks and social distancing; no shows and small gatherings — that it’s not a matter of foolishly and selfishly throwing them off, but simply living through them, living despite them. By doing so, even as we grapple with this new kind of chaos, we also arrive at new kinds of art, new kinds of lives. At least that’s the hope. But, man, breathing through an N95 mask takes some getting used to!

On a personal level that show will be, as you write in the liner notes, a “seminal experience,” but it must be gratifying — surreal perhaps? — to have something you did while in high school put back into the world for others to experience.

It is indeed gratifying and totally surreal to have this long-ago seminal experience put out into the world. Believe me, while we knew that fellow punks in the DC scene liked the band, and we had gone over well at our handful of out of town shows — as I recall, we played in New York City three times, Bridgeport, and Detroit — the band’s lasting impact, influence, resonance, or however you want to describe it, has always been a surprise. A welcome surprise, for sure, but a surprise. I mean, we knew were good, but we didn’t know we would last.

And, yes, the show was undoubtedly a very long time ago. But whereas the Faith/Void album, the Subject to Change EP, and even the first Faith demo have been out for a long time now, because this recording has never been released before, an event nearly forty years old possesses a newness nonetheless. At least to me!

How did this release come about?

Live at CBGB’s came about by Michael and John (Pastore of Outer Battery Records) hanging out discussing what tapes they’d each been digitizing. When Michael mentioned that he had a cassette off the soundboard of our show opening for the Bad Brains at CB’s, John made clear he really would like to put it out and, well, that was that. So, pretty simple. That serendipity once more.

Revisiting this material, were there any particular songs that took on new or different meaning for you?

I have to say that when I first listened to the tape I’d forgotten that we’d ever played “Steppin’ Stone” at all — in practice or at any show, let alone this one. I’d forgotten that we were already playing “Don’t Tell Me” and “Outlet,” as I thought those songs came along a bit later.

But to answer your question, I have to say that revisiting had me looking at our songs as a whole in terms of the band’s continued resonance. What is it about them that’s made them remain relevant, that’s made them still speak? The answer can, I think, be found in what J. Mascis recently said about the band: “The Faith were singing my life in their songs.” So, you could say, the personal becomes…if not universal, then at least appealing and applicable to other people, to many people.

In that light, lines like, “I know what I want and I take what I need” from “It’s Time”; “Never want to be trapped in your circles” from “Trapped”; “I’ve come too far to go back/I’m gonna find out what’s in the black” from “In The Black”; “Feel the pain inside of me/Suffering in agony” from “Nightmare”; and the questions from “What’s Wrong With Me?” — “Why do I care when you don’t?/Why can’t I see you don’t want me?/How come it’s me that’s always hurt?/How come it’s me that feels like shit?” — relay feelings and thoughts that people — teens, punks, and all the rest — can readily relate to. Add to that the sound of the songs, which express the anger, and frustration, and passion, and all the rest in Alec’s vocals, Michael’s guitar, Chris’s bass, and my drumming and you can begin to see why Faith has the fans that it does and why Live at CBGB’s has come out.

Like most other people with a grounding in the punk or hardcore music scenes, the liner notes express a lot of reverence for the Bad Brains. Did opening for them push this show into a higher, more kinetic gear for you? Not in the “want to impress our heroes” sense but just in the sense that energy feeds energy and greatness encourages greatness?

Totally, totally, totally. It was never a matter of impressing our heroes, but being inspired by them. I will always be in awe of the Bad Brains. Their precise rawness, their power, their tightness, their… Fill in the blank with what a band does to transform you and they were that. And I’m just talking about listening to Banned in D.C., their ROIR cassette that came out two months after this show. And live? Bad Brains shows were legendary then, of course. With their performances, they created this other world that didn’t need to grab you even though it did, since you were already grabbing it with the first chord. And that world was a place where you belonged, where you needed to be. Sure, it was loud and aggressive and unpredictable, but that was the point, along with being exhilarating and feeling invincible. You were with the band, you were in their songs, the punk tunes taking you to the brink, the reggae jams bringing you back.

As for that show, it wasn’t a situation where we felt compelled to up our game, as the saying goes. Adrenaline, amazement, luckiness, just the sheer I-can’t-believe-this-is-happening put us in that “higher” gear. Everything felt charged, intense: the sound, the lights, the stage, the crowd.

And even though, we knew, of course, that we were going to get blown off the stage by the Bad Brains, that didn’t matter: every band that opened for the Bad Brains got blown off the stage by them. But not every band opened for them.

And opening for them meant being able to see them sound-check and that was so, so special. Of course, the crowd responding to their songs added an incredible dimension to their shows. But seeing them sound check on their own, you saw that they were just as powerful, if not more so, since they didn’t need stage diving and slam dancing to be the best band around. Their formidable power — how could just a guitar, a bass, some drums, and vocals do that?! — just was there, visceral, unbound, pure. Just them playing, just us watching. What a privilege.

You just felt lucky to be associated with the Bad Brains. And here they had asked us not only to play with them — Us? Our third show? — but to do so at CB’s. Incredible. And on top of all that, they went along with us using their equipment. Incredibly cool. In light of the show taking place on December 26th, they had given us a wonderful Christmas present.

The DC scene was at the verge of a sharp, wild ascent that would prove highly influential across the globe — and Faith was there at ground zero. As you continued to make music and the world took note and DC blossomed and evolved, how did things change for you in the aftermath of the era this CBGB show captures? And how much does that moment of ignition continue to inform how you share and create?

Well, in light of this being our third show – our first, the month before, had been at a high school gym; our second, in early December, we opened for Black Flag at the 9:30 Club — I am happy to say we got tighter. Not Bad Brains tight, or Minor Threat tight, but tighter. And we came up with more songs. One, “Face to Face”, we worked out in one practice and performed the next night. We played more shows in DC, mostly with other DC bands. But we also played with the Bad Brains again, and we played with Dead Kennedys and other bands that I can’t recall. Best of all, we added Eddie (Janney) on guitar, so we got an even fuller, deeper sound. That’s why Subject To Change sounds so good. As for myself, I graduated from high school and was so happy with how things were going that I put off going to college by a year.

In regards to the DC scene taking off, it was wild to be a part of something that really began getting a lot of attention. So, you’d read about the scene in Thrasher and Maximum Rock and Roll or DC’s City Paper and even The Washington Post. You felt like, “We” — as in the DC scene — “must be doing something right!” At the same time, because it was happening to us — as in the DC scene — it seemed pretty normal. But it really wasn’t normal to have all these bands happening, and shows, and punks, and a label supporting the scene, and all the rest.

For me, playing the drums quickly came to mean being in a band that was part of a scene, that played shows, and recorded. If it wasn’t real like that, then forget it. Beyond that, being in the DC punk scene helped me realize that I could take myself seriously as an artist. And so a good many years later when I knew I wanted — no, needed — to write a book about my experiences as a New York City window cleaner, I did it. And the same with the fiction I’m working on now. Nothing should stop you, you know?

Finally, it’s a bit strange hearing such a vibrant record in the middle of a global pandemic that has all but halted live music. This, to me, is a fantastic reminder of how essential the live experience is and why it should be nurtured and rebuilt once this is over.

Experiencing live music is just as primal as wanting to play music. That sense of community, of communion, is so important to the musicians and the fans. You take it for granted and then — poof! — it’s gone. Such a loss; such a hole. It’s been amazing to see the remarkable ways that artists and audiences have responded to the pandemic. Online shows, socially distanced shows, songs worked on and simply put out there. You just see musicians and audiences seeking each other in any way they can.

I read about the UK’s first socially-distanced outdoor music festival that took place in August that featured 500 metal decks, or pods, for up to five people per deck, set six feet part; images of the event brought to mind the cover of the Pink Floyd album Momentary Lapse of Reason with all those empty beds in a field. So perhaps that’s a way to go.

I think that venues need to receive assistance, just as ways to safely put on shows need to be arrived at. For it’s more than just livelihoods at stake — musicians, club owners, roadies, and all the rest — part of what it means to be human is at stake as well.

The post Exclusive Interview: The Faith/Embrace Drummer Ivor Hanson Talks “Live at CBGBs” appeared first on Decibel Magazine.