EMG Pickups Announces All New E-Series Bass Pickups

EMG Pickups introduces the all-new E-Series lineof active bass pickups. Featuring the commonly used slim soapbar cap design, the E-Series pickups unlock a multitude of bass models for simple, drop-in EMG upgrades.Unlike any other EMG design, the E-Series pickups feature wide aperture coils withceramic magnets. This potent combination delivers powerful low end while retaining thecutting articulation that the modern bass player requires. Designed with versatility inmind, the E-Series can excel in a wide range of genres and play styles and areavailable in 4, 5, and 6 string sizes. Just like all EMG active pickups, the E-Series arefree from hum and buzz and include solderless wiring kits for DIY installation.For further tonal shaping, the E-Series pickups are compatible with EMG’s wide rangeof bass EQ’s and accessories, so the possibilities are virtually endless.Unlock the potential of your bass with the EMG E-Series pickups.Individual E-Series pickups start at $109.00, with sets starting at $209.00.EMG E4Whttps://www.emgpickups.com/bass/e-series/4-string-e-series.htmlEMG E5Whttps://www.emgpickups.com/bass/e-series/5-string-e-series.htmlEMG E6Whttps://www.emgpickups.com/bass/e-series/6-string-e-series.html

Read more »

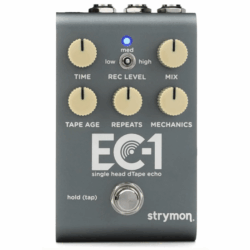

Strymon EC-1 Review

Though they are maligned for their fragility, I’d put the Echoplex tape echo up there among the greatest pieces of musical instrument design. They are totally inspiring tools—certainly in terms of their sound, but also for the mechanical means by which one manipulates and mangles tones. These days, several digital sound designers replicate the Echoplex’s warm, hazy, and mysterious sonic fingerprint with startlingly good results. But just like real fingerprints, the sonic signature of every Echoplex is a little bit different, and one of the most interesting facets of the Strymon EC-1 design is the departure point they used for inspiration.Rather than emulate the familiar and relatively common solid-state EP-3, Strymon used a tube-preamp-driven EP-2 as a launch pad—except that Strymon’s EP-2 was heavily modified by legendary amp man Cesar Diaz. In Strymon’s estimation, Diaz’ modifications added some characteristics of an EP-3 preamp to the EP-2 formula. In my experience (I’ve played EP-2s and EP-3s side by side and used the latter for comparison in this review) that could mean extra headroom or, in the worst cases, comparative brittleness. Strymon, for their part, says Diaz’ mods resulted in a warmer sort of EP-2 sound. Regardless of their design intent, the EC-1 sounds fantastic in many of the ways a great Echoplex might. The haze and degradation in each repeat sound and behave much like magnetic tape, shaving off high and high-mid spectrum detail as the echoes recede, and adding the dreamy, blurry ambience of a Gerhard Richter painting. But the EC-1 also does sound truly warmer than some of its rivals.Punch and FoggyThe EC-1 features two preamp modes. The default or “amber” mode emulates the modded preamp Strymon discovered in their EP-2. Somewhat paradoxically for a pedal that excels at simulating tape-signal degradation, it gives the pedal a punchy, airy ambience that can make other delays sound flat and one-dimensional. You can also add up to 6dB of boost, and one thing is certain; at these hotter settings the EC-1 is not a tape-delay emulation that will go missing in an ensemble performance. The second “green” preamp mode emulates a stock EP-2, and while it sounded awesome, it felt a little less fun and dimensional—at least after ripping away with the default mode. Both modes sound great with drive and distortion, however. And in the amber mode, the extra detail you hear also makes it feel more sensitive to picking and input dynamics.As is obligatory in most Echoplex emulations, the EC-1 offers excellent approximations of tape warble, tape wear, and recording input level effects. There is also stereo and MIDI functionality. In terms of price, the EC-1 inhabits an interesting position in a market full of top-performing Echoplex emulators. At $279, it’s $120 less than Universal Audio’s feature-rich Starlight Echo Station, $100 less than Strymon’s own El Capistan, and 80 bucks less than the Catalinbread Belle Epoch Deluxe. There are also excellent options in less expensive ranges, like the standard Belle Epoch ($209), Dunlop’s Echoplex pedal ($199), and UA’s Orion ($169). Though some of them offer more in terms of options and versatility, I’m not sure any of them can better the sounds of the EC-1. And certainly, the EC-1’s default mode offers a unique and exciting twist on EP-2 sounds that, while not vintage-correct in a technical sense, may offer more utility as a delay than the most perfectly executed Echoplex ever could.

Read more »

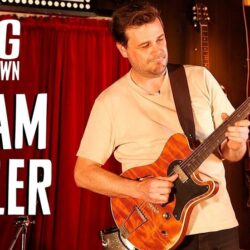

Adam Miller Rig Rundown

The prolific Australian guitarist brought his mastery to east Nashville, where we got a look at the gear he’s trusting overseas.Adam Miller has been compared to plenty of his most sacred influences—Tommy Emmanuel, Chet Atkins, Charlie Hunter, Bill Frissell—but he’s certainly carved a path of his own. This year alone, he’s released three records and undertook a U.S. tour to bring his delightful mix of jazz, groove, and beyond to eager listeners.Before his show at the Underdog in east Nashville, Miller took some time to show PG’s Chris Kies around his trusted tools for international touring, including a gorgeous custom Huber electric, a Collings acoustic, and some key items on loan.Calling a HuberThis custom-built Huber electric, by German luthier Nik Huber, was crafted over the last five years, working in elements of Miller’s previous Huber and several other designs. It has a heavily chambered mahogany back and redwood top, bolt-on maple neck, rosewood fretboard, trapeze tailpiece, and nylon saddles, plus Kloppmann Electrics mini humbuckers and a single 250k volume pot, which rolls off for a jazzy archtop sound. Miller strings it with D’Addario NYXLs (.011–.049s).Borrowed BariSince Miller can’t bring all his favorite instruments on tour, he often borrows guitars from local friends and fans on tour, like this baritone Novo Serus J.Collings CallingMiller bought this Collings acoustic at Gladesville Guitar Factory, just outside Sydney, about 10 years ago. He runs it with a Seymour Duncan Wavelength duo pickup system, but swapped out the kit’s undersaddle piece for soundboard transducers and modified “the circuit so they’re at a crossover, so you’re only hearing the bottom end of them and all the top end’s coming from the condenser mic.” He uses D’Addario Nickel Bronze (.012–0.53s) on his acoustic.Can I Bum a Studio Sig?Miller has been a Two-Rock devotee since 2007, and on one of his first trips to the U.S., he visited the factory and picked one up. He doesn’t travel with his unit, so he borrowed this one from Nashville legend Cory Congilio. For Miller, an amp is the soundboard for an electric guitar; if he doesn’t have a Two-Rock, he struggles.Adam Miller’s PedalboardMiller’s Collings runs into a Grace Design ALiX preamp, which helps him fine-tune his EQ and level out pickups with varying output when he switches instruments. For reverb, sometimes he’ll tap the Strymon Flint, but often he’ll let the front of house weave it in.Aside from the ALiX and Flint, Miller relies on a Vemuram Jan Ray, Free the Tone SOV-2 Overdrive, Chase Bliss Mood, and Line 6 DL4 Mk II.Seymour Duncan Wavelength DuoD’Addario NYXLD’Addario Nickel BronzeGrace Design ALiX preampLine 6 DL4 MkII Delay Modeler PedalStrymon Flint

Read more »

COLD SLITHER to Release New Song, “Cobra Island,” via the Decibel Flexi Series!

You’ve got until Sunday August 31 to secure an active deluxe Decibel subscription to ensure that a copy of G.I. Joe-stanning supergroup Cold Slither‘s new ripper “Cobra Island” becomes part of your vinyl collection.

Exhumed, Gruesome, Impaled and KMFDM members payed homage to their young by helping bring the fictional Cobra-backed metal band Cold Slither to life.

The post COLD SLITHER to Release New Song, “Cobra Island,” via the Decibel Flexi Series! appeared first on Decibel Magazine.

Album Premiere: Erosion – ‘Invasive Species’

Seven years after their punishing debut on Hydra Head Records, Vancouver’s Erosion return with Invasive Species—a filthy, blood-boiling follow-up that finds the band operating at peak ferocity.

The post Album Premiere: Erosion – ‘Invasive Species’ appeared first on Decibel Magazine.

Pick Your Pickup Giveaway!

You could WIN a JR “Daemonum” Set or REV Set from EMG Pickups in this all-new giveaway.

EMG Pickup Giveaway

EMG JR “Daemonum” SetJim Root, a long time user of the EMG 81/60 combo, began the process of developing a signature set well over three years ago. After trying various prototypes Root was inspired by a set of modified Retro Active pickups to tailor his tone. He settled on a set that gave him everything he loved from the 81/60 with the added benefits and versatility of the Retro Active design.Unlike traditional open coil pickups, both the bridge and neck pickup utilize stud poles. The fingerboard pickup uses ceramic studs giving it a clean high-end percussive tone. The bridge pickup has black steel poles and features a ceramic magnet, similar to the EMG 81. Both pickups feature custom Retro Active preamps exclusive to the Root set.Make sure to check the instructions for pickup measurements before purchasing to compare your existing pickups with EMG models.EMG Rev SetThis passive pickup set created for guitarist, songwriter and producer Prashant Aswani. The Revelation Set spent 2+ years in development that included testing in both recording and live playing sessions. After several variations EMG had designed an undeniably brilliant pair of humbuckers that delivered the clarity and definition usually found only in active pickups.This matched set has precision wound custom bobbins and alnico 2 magnets that create the perfect balance between neck and bridge positions. The alnico 2 magnets have just enough “give” to deliver that classic sponginess passive players crave without the muddiness usually associated with old school PAF-types. Aswani is known for his amazing style and tone and now has the perfect pickups to help him deliver every time.Make sure to check the instructions for pickup measurements before purchasing to compare your existing pickups with EMG models.

Read more »

A Low-Cost Gamma for the Gigging Guitarist

Before getting to the Gamma G50 ($199 street) amp that has solved a lot of problems in my professional life, I should explain my musical day-to-day. One month, I clocked gigs in Jewish old people’s homes for Holocaust survivors, followed by an outdoor concert backing Bootsy Collins. Then, three bluegrass gigs and five gigs with a horn section soul band. Most of those were powered by a mid ’80s Polytone Mini-Brute with a Muzizy 5-band EQ and a cheap reverb pedal. The Mini-Brute is the Dodge Dart of guitar amps—compact and unkillable. I loved that amp as I would a favorite uncle. And like my favorite uncle, it died, to nobody’s surprise, shortly after my 53rd birthday.I’ve tried different micro-amps. Since my electric life is low volume (mostly jazz or Latin music, with occasional klezmer thrown in), 50 watts is fine by me. If you live roadie-free as I always have (my painfully brief stint with NRBQ notwithstanding), the braggadocio about tone gives way to “fits in the car,” “isn’t hard to lift,” and—this is huge—“doesn’t break.”There are two schools of thought about amps: The first is that the amp completes the sound of your guitar, which is a Marshall aesthetic. The second is that your amp should sound like whatever you plug into it, maybe with a little reverb for dimension, and that’s Fender thinking. I am definitely a Fender thinker. My effects rack is minimal—reverb, tremolo, and analog delay (for rockabilly slapback). And the Muzizy EQ.In my formative years, the amps around my neighborhood were battered Supros, Silvertones, and Univoxes. The guitars were mostly Penco, Morris, Hondo II, Harmony, Silvertone, and unbranded Strat copies. It was how you made do until you could afford something decent.But inexpensive guitars improved. First lawsuit guitars, then Squier, whose Japan-built Telecasters surpassed their American-made counterparts. Now Harley-Benton et. al. have revolutionized the market.As a man old enough to recall the Dodge Dart, I look back with longing to the barebones interface of a Supro solid-state combo amp. Who makes that nowadays? Acoustic has been reborn as Acoustic Control Corporation. Their signature combo amp is the Gamma, available in either a 25- or 50-watt version. The 50 weighs 25 pounds, runs two channels, features a 4-position “voicing” selector that gives you your choice of metal, rock, blues, and clean. The 12″ True Blue speaker sounds close to a Celestion, so that’s not bad. The tone knobs are clean and sensitive, with neither dead spots nor sudden gains. The inherent sonic personality of this amp resembles an Ampeg Reverb Rocket (the 1×12 version), and it weighs less. Kind of miraculous for something with no tubes. Warm, quiet, and non-sterile. The control set? Voicing, volume dials for each channel, 3-band EQ, and drive.“If you live roadie-free as I always have (my painfully brief stint with NRBQ notwithstanding), the braggadocio about tone gives way to ‘fits in the car,’ ‘isn’t hard to lift,’ and—this is huge—‘doesn’t break.’”Out on the gig? The first night, I used it with Los Chicos del Mambo, a loud 20-piece band. The job was at the Paramount, a giant wooden room in Los Angeles, whose skilled soundman miraculously kept screaming trumpets from deafening the entire 90033 zip code. The bassist played out of a Laney 200H. I played my Harley-Benton CG-200CE electric classical through the Gamma 50, sans effects. And it cut. Headroom to burn.

The next day, same amp but different venue, band, and guitar. Band—Voodoo 5, the eight-piece exotica group I lead with my wife, vocalist Lena Marie Cardinale. The other instruments are flute, vibraphone, pedal-steel guitar, upright bass, and two Latin percussionists. Venue—the Redwood Bar, whose stage is a squeeze for eight. Guitar—an Indio DLX Plus, which is a Jazzmaster copy but with (huzzah!) a maple fretboard, plugged into my anemic effects rack.

The room is smaller, but with a long trajectory from the bandstand to the back. For this performance, I didn’t modify my guitar tone other than to hit the pickup switch. The Muzizy was set to its usual place, reverb on for the whole show, and I only hit the tremolo box on two songs. Guitar and amp doing basic duty.From Instagram videos, I heard what the audience heard through my $10 earbuds, giving me an un-glamourous idea of what went out into the room, and I am mightily impressed by how formidable the G50 is. Even in the battlefield recording conditions, the presence, reach, warmth, and clarity were unmistakable.Maybe I was going in search of the simpler operating procedures of my early musical life, but I really wanted an amp that boasts fewer knobs and delivers the character of whatever I plug into it. That it comes in at a price we can all afford and a weight we can all lift is gratifying to this old—old—pro.

Track Premiere: Seilies – ‘Before We Die’

Seilies want you to see this video “Before We Die.”

The post Track Premiere: Seilies – ‘Before We Die’ appeared first on Decibel Magazine.

Foot-Controlled Analog Delay?? | Black Mountain Roto Echo

PG contributor Tom Butwin walks us through a rugged, pedal‑board‑friendly delay that lets you shape time, feedback, and blend entirely with your foot. The Roto Echo features warm, gritty analog‑style echoes, intuitive real‑time control, and a design tough enough for full body weight. It sounds great on its own, but this wheel‐driven innovation opens up worlds of expressive possibilities.Black Mountain Roto-EchoThird Man Hardware and Black Mountain are excited to announce the innovative Roto-Echo delay pedal. Instead of tweaking delay parameters with your fingers, the pedal’sFreewheel® Technology allows players to change them with their feet in real-time as they play –a small change that leads to tons of creative possibilities.The Roto-Echo is built tough and players can put their full weight onto the pedal with noproblem. It’s the same size as a regular Boss-style guitar pedal, and fits on any pedal board.Key Features● Foot-Controlled Adjustments: Change Time, Feedback, or Blend while you play.● Analog-Style Delay: Warm, gritty echoes up to 600ms.● Rugged Build: Built to handle full body weight on stage.● True Bypass: Keeps your tone pure when switched off.● Play Sitting or Standing: Built for performance.● 9V, Center Negative Power● Morph feedback from short to infinite repeats● Ramp wet/dry mix for dramatic effect● Sweep delay time to bend and warble pitch, and so much more

Read more »

Voltage Cable Co.® Releases “Tele” Plug for the Voltage Vintage Coil® V2

Voltage Cable Co.® has introduced a new hardware option to its best-selling Voltage Vintage Coil® V2: a long-frame right-angle “Tele” plug by G&H USA. Purpose-built for recessed Tele guitar jacks and vintage-style guitars, this new plug ensures a tighter fit and improved seating depth – solving a long-standing problem for players using standard short right-angle connectors. Each cable continues to feature Voltage’s hallmark component stack: 21 AWG spiral-shielded conductors, Cardas Quad Eutectic silver solder, and the patented ISO-COAT® hermetic seal, now officially granted under Australian Standard Patent No. 2024204464 as of June 26, 2025. The result is an elite-class instrument cable with lifetime-grade durability and signal reliability, built specifically for working musicians.The Voltage Vintage Coil® V2 is available in seven vintage-inspired colors and ships globally.Available now at $99 USD MAP: voltagecableco.com/products/coiled-guitar-cable-voltage-vintage-coil-v2

Read more »