GW Editor-in-Chief Damian Fanelli’s favorite riffs (and a new way to play the Beatles’ “Something”)

In this stupendously rare video, Damian Fanelli — Guitar World magazine’s editor-in-chief since 2018 — plays and discusses some of the guitar riffs that changed his life. Get ready for…

Read more »Track Premiere: Carnage Inc – ‘Epik’

Play thrash or die with India’s Carnage Inc.

The post Track Premiere: Carnage Inc – ‘Epik’ appeared first on Decibel Magazine.

Source Audio Launches theEncounter Ambient Delay+Reverb

Source Audio, a leader in next-generation guitar and bass effects pedals, proudly introduces the Encounter Ambient Delay+Reverb, a fully loaded, dual-engine effects pedal designed to unlock immersive, atmospheric soundscapes. Building upon the legacy of Source Audio’s award-winning Collider Delay+Reverb, the Encounter features dual signal processing, allowing users to combine any two of the pedal’s six delay and six reverb effects. Where the Collider focused on classic delay and reverb effects, Encounter ventures into uncharted tonal territory, delivering new, otherworldly effects for guitar, bass, synth, and adventurous sound designers of all kinds.“You asked, so we delivered!” says Roger Smith, President of Source Audio. “Ever since the release of the Collider Delay+Reverb, players have asked us to push further — into more adventurous, exploratory delay and reverb textures. Encounter answers that call. It opens up an expansive new universe of sonic possibility, combining reimagined classics with brand-new algorithms that explore both the familiar and the beautifully unknown.”At the heart of the Encounter are six delay and six reverb engines that can be used individually or combined in pairs — this includes dual delay and dual reverb setups. Users can route dual effect combinations in series, parallel, or split stereo, with independent footswitch control for each engine, effectively offering the power of two pedals in one easy-to-navigate enclosure. Stereo ins and outs, full MIDI implementation, 8 onboard preset slots (128 presets with MIDI), external expression control, and seamless integration with Source Audio’s free Neuro 3 editing software for iOS, Android, macOS, and Windows further elevate the pedal’s flexibility and creative potential.The Encounter’s effects collection features brand-new engines such as Hypersphere, a gravity-defying ambient reverb inspired by infinite spatial reflections, Kaleidoscope, a cascading, harp-like delay effect, and Shimmers, a rich, dual-pitched shimmer reverb designed for lush harmonic layering.Modernized favorites from Source Audio’s acclaimed Ventris Dual Reverb and Nemesis Delay ADT also make a return — Reverse, Lo-Fi, Trem Verb, and Swell reverbs, along with Helix, Drum Echo, Noise Tape (based on the Roland Space Echo) and Resonant delays — all reimagined with expanded parameter control.In addition, musicians can preview and explore the sounds and editing capabilities of the Encounter before purchasing the pedal, using the Neuro 3’s new SoundCheck™ feature. Neuro 3 is Source Audio’s entirely free effects editing, preset sharing, and organizing software. SoundCheck features prerecorded, unaffected guitar, bass, keyboard, and drum loops that can be played through bit-perfect replications of Source Audio One Series pedals. Users can audition presets or use the effect editor and hear changes in real-time, using only a smartphone or computer.

Read more »

Brickhouse Toneworks Introduces Mason Deluxe P.A.F. Humbuckers

Adding to the company’s lineup of premium US-made pickups, Brickhouse Toneworks has introduced the Mason Deluxe P.A.F. pickup. Available individually or in matched sets, the Mason Deluxe delivers the classic, exquisitely balanced tone of a vintage 1960s P.A.F. humbucker with added bite. They are a direct drop-in replacement for standard sized humbuckers.Sporting AlNiCo 4 magnets for enhanced attack and articulation, the Mason Deluxe P.A.F. has the clarity of a lower wind with the power of a fuller wind. Pickup master David Shepherd designed the pickup with two slightly different wire thicknesses on each coil, along with carefully calibrated asymmetrical coils, to bring out the maximum frequencies and dynamic range possible.Expanding on the legacy of Brickhouse Toneworks’ highly regarded 1960 P.A.F. and Semi 60 P.A.F. humbuckers, the Mason Deluxe P.A.F.’s deliver a unique tonal profile characterized by a chimey, bell-like clarity and exceptional articulation. The sound is both smooth and responsive, with a dynamic range that allows for a sweet, rolled-off tone as well as a powerful, aggressive distortion. A defining feature is the rich, harmonic overtones that bloom and sustain, providing a heightened sense of depth and dimensionality. The pickups also exhibit a slight microphonic effect, which enhances pick attack definition. This results in a complex, yet clear sound—fat and woody in the neck position, and sparkling with pronounced punch and tonal definition in the bridge.

The result: an extraordinarily responsive P.A.F. humbucker with a transparent and open sound, allowing the guitar and player’s natural tone to be the star of the show.Key Features of the Mason Deluxe:AlNiCo 4 Roughcast Long Bar Magnets, Unpotted CoilsVintage Correct Long Leg Frames and Butyrate Plastic BobbinsVintage Correct Alloys, Coil Wire and Braided Single Conductor LeadsVintage Correct Hand Ground, Hand Buffed P.A.F. CoversDC Resistance – Bridge: 8.1k (Average)DC Resistance – Neck: 7k (Average)Made in the USA with premium quality materialsThe Brickhouse Toneworks Mason Deluxe P.A.F. street price starts at $195 each and starts at $390 per set. Visit www.brickhousetone.com or contact info@brickhousetone.com for more information and order yours directly.

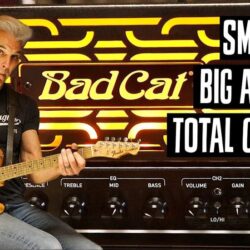

$1,299 Tube Amp That Does It ALL?! | Bad Cat Ocelot Amp Demo

Mad Cat!—The 2 X EL84, 20-watt Ocelot can breathe fire when it’s not sounding silky smooth. The Ocelot brings together the warmth of pure analog tube circuitry with advanced digital features, redefining what’s possible in a small-format amp. Whether you’re recording at home, gigging, or practicing silently with headphones, the Ocelot adapts to your environment without ever compromising your tone. Channel 1 features sparkling, high-headroom cleans with the ability to nudge into rich edge-of-breakup tones via a Hi/Lo mode switch. Channel 2 brings tight, punchy crunch and full-bodied, high-gain saturation—with articulate response and massive sustain. Each channel has its own volume control, and the amp includes shared Treble, Mid, Bass, and Presence EQ for easy tone shaping. Two Notes Torpedo DynIR integration with six onboard virtual cabinet presets from the official Bad Cat DynIR Pack. Selectable Power Modes – Choose between 20W for full punch or 1W for quiet playing. XLR and Headphone Outs – For silent practice or direct-to-DAW recording, complete with Cab Sim and adjustable Cab Level control. Buffered Effects Loop – Keep your pedals sounding pristine and punchy. USB-C Port – For firmware updates and remote editing via Two notes Torpedo Remote software. MIDI Control – Full MIDI implementation for switching channels, modes, and cab presets on the fly. And thanks to its internal speaker load, you can use the Ocelot without an external cabinet—perfect for late-night jams or tracking in a silent setup.

Read more »Blast Worship: Nasum

Taking a look at grind legends Nasum’s 1998’s classic Inhale/Exhale in its Inhaled/Exhaled/Revived form out via Relapse next month.

The post Blast Worship: Nasum appeared first on Decibel Magazine.

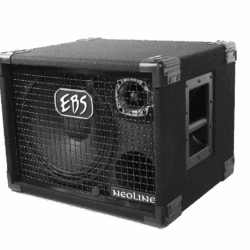

EBS updates NeoLine 112 Cabinet with deeper dimensions and improved sound

EBS is proud to unveil the newly enhanced NeoLine 112 Mk2 bass cabinet, now shipping with key upgrades that bring even more power, low-end, and reliability to the stage.The first significant change: the cabinet is now 4 inches deeper, offering a noticeable improvement in low-end response, projection, and overall tonal richness. This enhancement ensures that today’s bassists get the punch and presence they need from a compact cabinet, whether they’re in the studio, on tour, or pushing the limits live.Second, EBS has swapped out the previous flip handles in favor of a single heavy-duty deep-dish handle. This small but significant upgrade helps eliminate the risk of rattling noise, making the cab perform securely even at high volumes, while also improving durability and ease of transport. Third, the high-performance tweeter is now isolated and sealed from the rest of the cabinet, which also helps to reduce the risk of noise due to the sound pressure within the cabinet.Despite the deeper cabinet, and due to the Neodymium speakers and choice of wood, it remains a lightweight cabinet, weighing in at 14.35 kg (31.6 lb).Already a favorite for its lightweight construction and road-ready build, the updated NeoLine 112 (Mk2) now delivers even greater performance with no compromises. It’s a compact speaker for serious players. Despite the improvements, the price remains intact.The updated NeoLine 112 Mk2 is available now.Find out more at https://ebssweden.com/cabs/neoline/

Read more »

Fender Introduces LE Vintera II Road Worn

Today, Fender is expanding its acclaimed Vintera® II series with a Limited Edition Road Worn® lineup, era-correct classics from the ‘50s and ‘60s pair vintage-inspired designs and modern upgrades with the lived-in look of a well-loved instrument. Each model features a new subtle aging process—light checking, gentle wear patterns, and a semi-gloss finish—delivering unmistakable vintage feel and unmatched sound of a classic Fender®.Limited Edition Vintera® II Road Worn® ‘60s Stratocaster®($1,599.99 USD, £1,349 GBP, €1,599 EUR, $2,649 AUD, ¥269,500 JPY)Featuring a variety of vintage colors finished in Road Worn® aged nitrocellulose lacquer, the Vintera® II Road Worn® ‘60s Stratocaster® recreates the look and feel of a well-played classic. The limited Road Worn models are enhanced with a new subtle aging process combining light checking, gentle wear patterns and a semi-gloss finish, while maintaining the authentic broken-in feel players love about vintage Fenders. The ‘60s “C”-shape maple neck with 7.25” radius rosewood fingerboard and vintage-tall frets provides supreme comfort and outstanding feel. Under the hood, you’ll find a trio of vintage-style ‘60s pickups that deliver all the warm, sparkling tones that made Fender® famous. Other features include a synchronized tremolo with bent steel saddles for expressive vibrato and vintage-style tuning machines for enhanced tuning stability. Options include Rosewood Fingerboard in Sonic Blue and Maple Fingerboard in Black.Fender Vintera II Road Worn ’60s Stratocaster Maple Fingerboard Electric Guitar

Limited Edition Vintera® II Road Worn® ‘60s Telecaster®($1,599.99 USD, £1,349 GBP, €1,599 EUR, $2,649 AUD, ¥269,500 JPY) Featuring a variety of vintage colors finished in Road Worn® aged nitrocellulose lacquer, the Vintera® II Road Worn® ‘60s Telecaster® recreates the look and feel of a well-played classic. The limited Road Worn models are enhanced with a new subtle aging process combining light checking, gentle wear patterns and a semi-gloss finish, while maintaining the authentic broken-in feel players love about vintage Fenders. The ‘60s “C”-shape maple neck with 7.25” radius rosewood fingerboard and vintage-tall frets provides supreme comfort and outstanding feel. Under the hood, you’ll find a pair of vintage-style ‘60s pickups that deliver all the crystal-clear chime and raw, steely twang that made Fender® famous. Other features include a vintage-style 3-saddle bridge with slotted steel saddles and vintage-style tuning machines for enhanced tuning stability. Options include Rosewood Fingerboard in Burgundy Mist Metallic and Maple Fingerboard in Blonde.Fender Vintera II Road Worn ’60s Telecaster Rosewood Fingerboard Electric Guitar

Limited Edition Vintera® II Road Worn® ‘50s Jazzmaster®($1,699.99 USD, £1,399 GBP, €1,649 EUR, $2,799 AUD, ¥275,000 JPY) Featuring a variety of vintage colors finished in Road Worn® aged nitrocellulose lacquer, the Vintera® II Road Worn® ‘50s Jazzmaster® recreates the look and feel of a well-played classic. The limited Road Worn models are enhanced with a new subtle aging process combining light checking, gentle wear patterns and a semi-gloss finish, while maintaining the authentic broken-in feel players love about vintage Fenders. The ‘50s “C”-shape maple neck with 7.25” radius rosewood fingerboard and vintage-tall frets provides supreme comfort and outstanding feel. Under the hood, you’ll find a pair of vintage-style ‘50s single-coil pickups that deliver all the sweet and sparkling, warm and woody tone that made Fender® famous. Other features include a vintage-style floating tremolo for expressive vibrato and vintage-style tuning machines for enhanced tuning stability. Options include Rosewood Fingerboard in 3-Color Sunburst and Rosewood Fingerboard in Fiesta Red.Limited Edition Vintera® II Road Worn® ‘60s Precision Bass®($1,599.99 USD, £1,399 GBP, €1,649 EUR, $2,649 AUD, ¥269,500 JPY) Featuring a variety of vintage colors finished in Road Worn® aged nitrocellulose lacquer, the Vintera® II Road Worn® ‘60s Precision Bass® recreates the look and feel of a well-played classic. The limited Road Worn models are enhanced with a new subtle aging process combining light checking, gentle wear patterns and a semi-gloss finish, while maintaining the authentic broken-in feel players love about vintage Fenders. The ‘60s “C”-shape maple neck with 7.25” radius rosewood fingerboard and vintage-tall frets provides supreme comfort and outstanding feel. Under the hood, you’ll find a vintage-style ‘60s split-coil Precision pickup that delivers all the warm, dynamic and powerful tone that made Fender® famous. The vintage-style 4-saddle bridge and vintage-style tuning machines provide classic looks with enhanced intonation and tuning stability to complete the package. Options include Rosewood Fingerboard in Fiesta Red and Charcoal Frost Metallic.

Read more »Tomas Lindberg (1972 -2025)

The legendary At the Gates frontman Tomas Lindberg has lost his battle with oral cancer at 52.

The post Tomas Lindberg (1972 -2025) appeared first on Decibel Magazine.

Gibson Custom Introduces Five New Murphy Lab Light Aged Acoustics

Gibson is proud to introduce five new acoustic reissues for the Gibson Custom Murphy Lab Light Aged acoustic collection, delivering well-worn favorites, built brand new, with the look, tone, and played-in feel of cherished vintage originals.Each one of the five new additions to the Gibson Custom Murphy Lab Light Aged acoustic collection is a masterfully crafted reproduction of a cherished Gibson acoustic guitar model from Gibson’s first Golden Era. The Murphy Lab Light Aged acoustic lineup from Gibson Custom all feature either red spruce or Sitka spruce tops that have been thermally aged to give them the sound of a well-seasoned vintage guitar. The new additions to our Murphy Lab Light Aged lineup of vintage acoustic reissue models feature light lacquer checking, light dings, pick trails, and rounded fretboard edges, giving them the tone, look, and played-in feel of cherished vintage originals. Gibson Custom Murphy Lab Light Aged acoustic guitars are well-worn favorites, built brand new.Explore the full Gibson Custom Murphy Lab Light Aged acoustic collection, now available worldwide on Gibson.com HERE.Each acoustic guitar in the Murphy Lab Light Aged collection comes with an era-correct hardshell guitar case that corresponds with the style of case that was in use when that model was released, adding to the vintage ownership experience.1929 Nick Lucas Special Light AgedA small-bodied legend with a big voiceNick Lucas, known as “The Crooning Troubadour,” was a pioneering entertainer of the 1920s—one of the first to record guitar solos and perform with a guitar on the radio. His influence helped elevate the guitar as both a solo and accompaniment instrument. In 1926, Gibson honored Lucas’s request for a custom design, resulting in the Nick Lucas Special—the company’s first artist signature model, featuring a deeper body for enhanced bass response and tonal richness.Now, Gibson Custom proudly introduces the 1929 Nick Lucas Special Light Aged, a stunning recreation of this historic model. Built with a deeper mahogany body shaped like the L-00, it features a thermally aged red spruce top, gold sparkle multi-ply binding, and a matching L-2 style rosette. The mahogany neck joins the body at the 12th fret and has a C-shaped profile. The bound rosewood fretboard is equipped with 20 frets and is adorned with mother-of-pearl Nick Lucas inlays with engraved details. Gold Waverly tuners with ivoroid oval buttons are installed on the headstock, which also features a vintage-style “The Gibson” logo in mother-of-pearl. Finished in Argentine Grey with Murphy Lab Light Aging, it captures the look and feel of a well-loved original. Housed in a Red Line-style case, this model delivers timeless tone and unmatched character.1963 Dove Light Aged:All the tone, charm, and character of a vintage Dove—rebornFirst introduced in 1962, the Gibson Dove™ quickly became an icon of the square-shoulder acoustic family, following the Hummingbird™. With its bold voice and distinctive look, the Dove has been favored by legends like Elvis, Tom Petty, and Alex Lifeson. Now, Gibson Custom proudly presents the 1963 Dove Light Aged—a meticulous recreation of the early Dove models, crafted to deliver vintage tone and feel in a brand-new instrument.Featuring a thermally aged Sitka spruce top with traditional scalloped X-bracing and beautifully flamed maple back and sides in a Cherry finish, this Dove sings with clarity and power. The mahogany neck has a comfortable Round profile, paired with an Indian rosewood fretboard adorned with mother-of-pearl parallelogram inlays. A longer 25.5” scale length and maple body give it a bright, full voice that stands apart from the Hummingbird.Details like the rosewood Dove bridge with inlaid doves, engraved pickguard, and Kluson® Waffleback tuners complete the vintage aesthetic. Lightly aged by the Murphy Lab, it offers the look and feel of a well-loved original and comes housed in a vintage-style black hardshell case for the full Gibson Custom experience.1955 J-45 Light Aged:A faithful tribute to the mid-50s WorkhorseFirst introduced in 1942, the Gibson J-45™ quickly earned its nickname, “The Workhorse,” for its straightforward design, warm tone, and unmatched versatility. By 1955, key updates—like a longer fretboard with 20 frets and a larger pickguard—helped define the model’s enduring legacy. Today, it remains one of the most recorded and best-selling acoustic guitars of all time.The 1955 J-45 Light Aged from Gibson Custom is a masterfully handcrafted recreation of this pivotal model, built in Bozeman, Montana. It features a round-shoulder mahogany body with a thermally aged Sitka spruce top and traditional X-bracing installed with hide glue for vintage tone and resonance. The mahogany neck has a comfortable Round profile and is joined with a compound dovetail neck joint. A rosewood fretboard with mother-of-pearl dot inlays, bone nut and saddle, and vintage-style Grover® strap tuners complete the classic look.Finished with Murphy Lab’s Light Aging treatment and lightly aged hardware, it captures the feel of a well-played original. Packaged in a 1950s-style Lifton™ hardshell case, the 1955 J-45 Light Aged delivers the authentic tone, vibe, and craftsmanship of Gibson’s Golden Era.Pre-War SJ-200 Rosewood Light Aged:All the vibe, feel, and vintage allure of the rare rosewood Pre-War Super JumboOriginally introduced in 1937, the Gibson SJ-200™ quickly earned its title as “the King of the Flat-Tops” thanks to its bold sound, impressive projection, and commanding presence. Early models featured rosewood back and sides, but due to limited demand during the post-Depression era, production numbers remained low—making these early rosewood-bodied SJ-200s highly sought-after by collectors today. Gibson Custom now proudly presents the Pre-War SJ-200 Rosewood Light Aged, a meticulous recreation of those rare originals. It features a thermally aged red spruce top with traditional scalloped X-bracing, rosewood back and sides with a three-rope marquetry strip, and ornate multi-ply binding throughout. The AAA maple neck includes a walnut stringer and stinger detail, while the ebony fretboard and bridge are adorned with mother-of-pearl inlays. Gold Grover® Imperial™ tuners and a tortoise pickguard with multi-colored dots complete the look.Finished with Murphy Lab’s Light Aging treatment and housed in a period-correct Red Line case, this model captures the spirit and craftsmanship of Gibson’s Golden Era—delivering vintage tone, feel, and aesthetic in a stunning modern build.1957 SJ-200 Light Aged:All the vibe, feel, and vintage allure of the iconic 1950s Super JumboIntroduced in 1937, the Gibson SJ-200 earned its reputation as “the King of the Flat-Tops” for its bold tone, powerful projection, and striking presence. By 1947, maple replaced rosewood for the back and sides, and the SJ-200 became a favorite among legends across genres—from Hollywood cowboys to rock royalty. Today, vintage 1950s models are prized by collectors.Gibson Custom now presents the 1957 SJ-200 Light Aged, a faithful recreation of this celebrated era. It features a thermally aged Sitka spruce top with scalloped X-bracing installed using hide glue, AAA flamed maple back and sides with a checkerboard marquetry strip, and ornate multi-ply binding. The AAA maple neck includes a walnut stringer and stinger detail, while the rosewood fretboard and Moustache™ bridge are adorned with mother-of-pearl inlays. Gold Gotoh® tuners and a classic tortoise pickguard complete the vintage aesthetic.Finished with Murphy Lab’s Light Aging treatment and paired with lightly aged hardware, this model captures the look and feel of a well-played original. It comes housed in a period-correct 1950s-style Lifton™ case, delivering an authentic vintage experience only Gibson Custom can offer.

Read more »